National Memorial for Peace and Justice offers a stark reminder of a painful past

Published 12:00 am Sunday, August 12, 2018

By Maggie Blackwell

For the Salisbury Post

In early August, I traveled to my hometown of Montgomery, Alabama, to visit the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

The memorial is the culmination of work started in 2010 by the Equal Justice Initiative, led by local attorney Bryan Stevenson. EJI developed both The Legacy Museum and the memorial so Americans can explore our history of slavery and lynching. The premise is that only by facing our history and understanding it can we avoid re-living it.

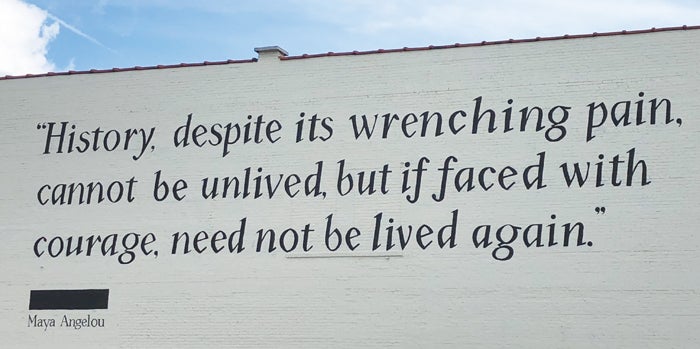

A quotation by Maya Angelou to that effect is on the wall of the museum: “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

I visited the memorial on a balmy, cloudy day. With a temperature at only 88 degrees, I expected to be cool, but there are no Carolina breezes in Montgomery. The humidity was 88 percent, and we were all hot and sweaty.

There’s a meditation garden before the entrance, and it’s beautifully landscaped but offers no shade. With the looming presence of the memorial, it’s hard to take time to enjoy the flowers.

Little vignettes like tell the ongoing story of African-Americans. A wall is built with bricks that were hand-made by slaves for a theater built in Montgomery in 1860. As the placard says, the bricks, having lasted more than 150 years, are a testament to their skill.

The graphic sculpture that’s central to the memorial is painful to look at. I had to remind myself that my own pain is nothing in comparison to being sold or beaten, losing a child, or being lynched.

The first glimpse of the memorial is stark. It’s tall – 12 feet or higher – with metal pillars suspended from the ceiling. There is a pillar for each county in the U.S. that had documented lynchings. Looking down a row of pillars, one is horrified by the sheer quantity. Most pillars represent more than one person, some many more.

The structure is a giant square, with four massive alleys of pillars enclosing a quad of green space. With the entrance on the northwest corner of the property, it takes quite some time to find Rowan County. It’s in the southeast corner, diametrically opposite the entrance.

Pillars are oddly organized alphabetically in spirals around the complex.

I cannot overstate the overwhelming quantity of inscribed names.

The campus of the memorial has higher and lower elevations, a little unusual for mostly flat Montgomery. Because of the rolling hill where it’s situated, some pillars are close to the ground and some far from it.

Pillars near the entrance are just an inch or two from the ground. The Rowan County pillar hangs high with the bottom about 20 feet in the air.

Near the exit, a breezeway with a wall of water offers emotional relief to visitors. Sheila Brown Nolen from Atlanta felt the water for several moments to enjoy a respite.

I met people from Detroit, Atlanta, Pittsburgh, Jacksonville, Dayton – all who had come a long way to see this memorial to people who never thought their names would be remembered.

An African-American bus driver from Raleigh told me nothing could shock him. “I’ve been living this history all my life, ma’am.”

Outside is a yard of twin pillars laid horizontally, each corresponding to a pillar inside. These pillars are available for removal to their home counties to pay homage to their own victims.