What are some of your favorite books?

Published 12:00 am Sunday, May 27, 2018

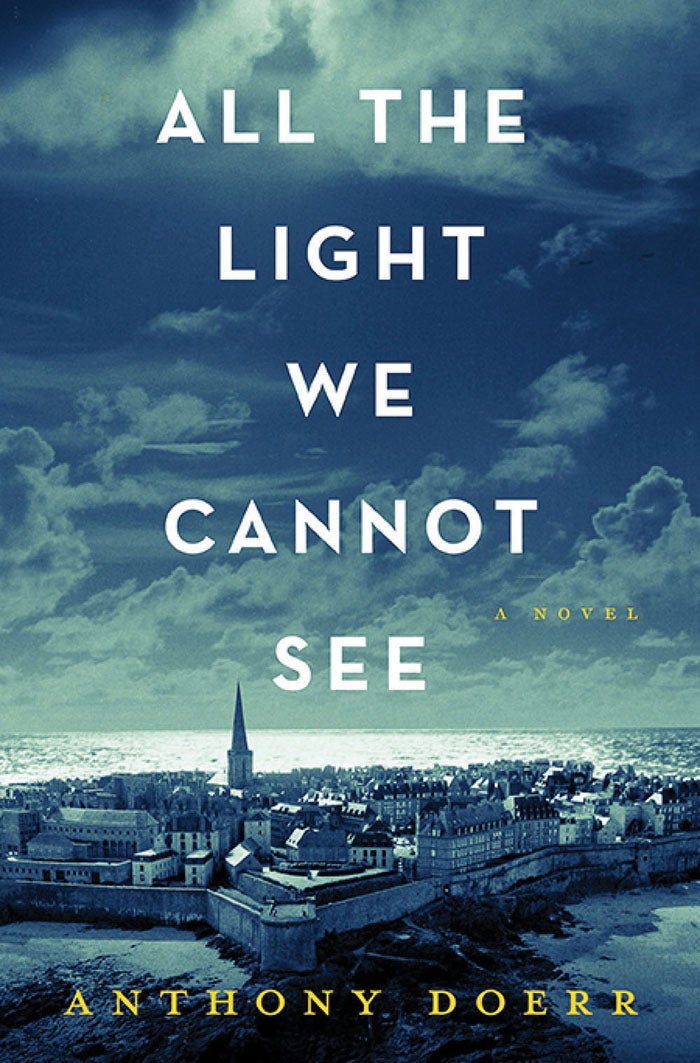

- Anthony Doerr, also a short story writer, has written an expansive and engrossing novel.

Have you been keeping up with The Great American Read online and on PBS?

We published the list of 100 books the program named as America’s favorites on April 22 to prepare you for the first event, a program on May 22 that talked to celebrities and authors about their favorite books — at least the ones on the list.

If you join the Facebook discussions, you’ll find many interesting alternative nominations. And you’ll see a lot of memories of the first time someone read one of the books on the list.

I noticed that many of the 100 books were ones I had read in school, from elementary to college. Of course, we’re different readers when we’re younger, and not every book delights us as much now as it did then. For me, “1984” was still a fascinating and disturbing book when I recently reread it, because a lot of the scary future Orwell predicted is already happening. Plus, I understood the consequences more as an adult.

“Wuthering Heights” seemed so romantic to me then. Now, Heathcliff comes across as a sociopath.

I will always love “The Little Prince,” by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. I read it at a very difficult time in my life, and it still resonates. It’s the perfect gift for any age.

“Frankenstein,” which I knew only from movies, was a revelation when I read the book. The monster is not a mumbling, stumbling association of assorted parts. The monster is a hybrid human, with deep thoughts and feelings and the rage that comes from being different and forever alone. And Frankenstein comes across not as a brilliant scientist, but a broken, troubled, desperate man.

There were books on the list I would not read, like “Fifty Shades of Grey” and “The Notebook.”

I’m not particularly interested in “The Twilight Saga” or “The Hunger Games,” though I devoured “The Lord of the Rings” and “Dune” when I was younger and didn’t have so many other things demanding my attention. I even memorized the litany against fear from “Dune” — “I must not fear./ Fear is the mind-killer./ Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration./ I will face my fear./ I will permit it to pass over me and through me./ And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path./ Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain.”

So, without fear, I made a list of some of my favorite books — the first few that immediately sprang to mind. Some of my other favorite books are already on The Great American Read list.

In my adult reading, these books, in no order whatsoever, are the ones I think of again and again and recommend to others.

“All the Light We Cannot See,” by Anthony Doerr;

“Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close,” by Jonathan Safran Foer;

“Lincoln in the Bardo,” by George Saunders;

“Olive Kitteridge,” “My Name is Lucy Barton,” “Anything is Possible,” by Elizabeth Strout;

“Let the Great World Spin,” “Transatlantic,” “Thirteen Ways of Looking,” by Colum McCann;

“The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet” and “Cloud Atlas” by David Mitchell;

“The Satanic Verses” and “Midnight’s Children,” by Salman Rushdie;

“The Lacuna,” by Barbara Kingsolver.

I fell completely in love with the blind French girl in “All the Light We Cannot See,” and the troubled boy indoctrinated by Hitler Youth. It looked at World War II — at the children, through a fictional lens — and not at armies or the millions of tragedies. Doerr tells this story using ugly truths and ethereal imagination.

Jonathan Safran Foer broke my heart over and over in “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close,” about a boy searching for the lock his father left the key to. His father died in the 9/11 terror attacks. It delves deeply into the horrors of war and terror, with a searing sub plot. Plus, the construction of the book, with photographs, visual gut-punches and more, is so different.

A lot of critics hated it. They said it was too “cute” and used tricks that had been done before by better authors. The movie was a real disappointment, at least for me.

“Lincoln in the Bardo” would easily make my top 10 list. The style is so unusual — using the dead as a Greek chorus, creating the bardo — a place sort of like purgatory, with extraordinary inhabitants whose exaggerated features speak to their obsessions in life. Then there’s the contrast with the broken-hearted father reluctant to leave his beloved son in a mausoleum. Brilliantly constructed.

I enjoy everything Elizabeth Strout writes. I picked three of my favorites. Strout can delve into the mind in the most subtle way. She treats relationships like the fragile and precious things they are, and again, breaks your heart.

She leaves much unsaid, but understood.

Colum McCann came here for Catawba College’s Brady Author’s Symposium a few years ago. I read “Let the Great World Spin” then, and many others, including “Zoli,” since. He has such skill with words, using them carefully, lovingly, and to such great effect. The minute I met him, I was hooked. He has the comic/tragic appeal of the Irish.

David Mitchell has written nine novels, and they are all challenging. The first one I read, “The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet,” taught me so much about Dutch trade with Japan, and was populated by characters so different and so intriguing, it was hard to put down.

We have said often in my book club, “I wish we could find another Jaob de Zoet.”

“Cloud Atlas” is another challenge altogether, as the novel shifts from a fantasy to a failed utopia, to a world destroyed and rebuilding. Is it science fiction? Maybe. Fantasy? For some. It’s a huge meal of courses too exotic to name and worth the effort it takes to get through it.

Salman Rushdie’s books are often challenging as well, and the two I most enjoyed were “Satanic Verses” and “Midnight’s Children,” both full of spectacle, mythology, ancient history and outrageous imagination.

“The Lacuna” opened up the art world of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera to me, and the exile story of Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. Historical fiction, done well, can teach so much, as long as you understand where the facts end and the invention begins.

These are books I say you have to stand up to read. Pay attention, take notes if you have to. They require a long and careful chew. And you will feel rewarded.

All these books on my list have one thing in common — uncommon writing.