Q&A, ‘Dreamland’ author Sam Quinones: Opiates’ catastrophic impact

Published 12:00 am Saturday, May 5, 2018

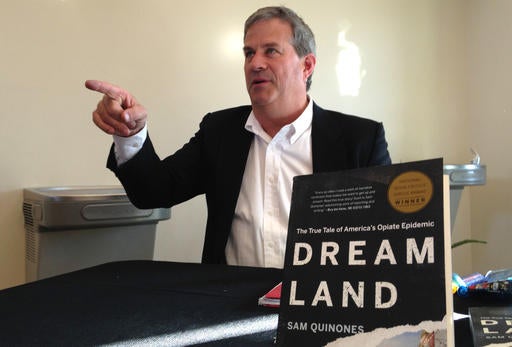

- Author Sam Quinones signs copies of his book "Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic" in Albuquerque, N.M., in 2016. Quinones, a recent winner of National Book Critics Circle Award, spoke about the resurgence of heroin and other opiates in the United States AP Photo/Mary Hudetz

Sam Quinones is determined to raise awareness of the U.S. opioid epidemic and its causes.

His book tells the story — “Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic.” (See a review on Page 5D.)

Many threads come together to create the frightening tapestry of this epidemic.

There was Xalisco, a Mexican area whose poverty pushed young men to find success the most expedient way they could — selling black tar heroin in the United States, conveniently delivering it to more and more customers.

There was the pharmaceutical industry, aggressively marketing painkillers to doctors looking for solutions to patients’ pain.

And there were — and are — the opioid addicts, compelled to use the drug over and over and over again, no matter what the cost. Family. Job. Life.

The impact has been devastating. More than 63,600 people died of drug overdoses in the United States in 2016 — more than died in traffic accidents or shootings.

In Rowan County, 36 people died of opiate overdoses in 2016 — again, more than were shot dead or killed on our roads.

Quinones, a journalist, author and storyteller, will be in Salisbury on May 15 as a presenter at the Second Annual Rowan County Opioid Forum.

The forum is a joint effort by Rowan County Public Health, the Center for Prevention Services, Rowan County, Youth Substance Use Prevention (YSUP) Rowan and Cardinal Innovations Healthcare.

In advance of the forum, Quinones gave the Post a Q&A interview about his book, the epidemic and the search for solutions. This is an edited transcript of that conversation:

Q: How long did it take you to do all the research for your book?

A: Technically, it took me about two and a half, three years. The truth is, I never would have come across this idea for this story had it not been for the fact that I’d already spent 10 years in Mexico. I came to this topic with a lot of background that is not necessarily counted in how many months it took to write the book.

There’s a whole learning curve to Mexico that I had already scaled by the time I came upon this and was one of the reasons I discovered it and ran with it.

My first interest was to write about Mexico and heroin. I didn’t know anything about pills and pain management at all.

Q: A person could come away from the book feeling that Big Pharma is really to blame for a lot of this, for misleading doctors or not warning them how addictive some of their products were. Do you think that’s accurate?

A: They share a big part of the blame, yes, but there’s a whole lot more to it. There’s our own desire as American health consumers to be fixed, to have something easy, to not actually have to do the hard work of being healthy or getting in shape, eating better, exercising more, being more choosy about what you put in your body. … Meanwhile, we demanded miracles from doctors.

I think doctors were also very eager, because they getting pressure from us, because it was easy to get patients out of their appointment rounds when you offer them a pill. Here you go, a pill. Boom, you’re on your way. I don’t have to deal with you any more.

I don’t subscribe to the bogeyman theory of history, where there’s a villain and you know who that villain is and you can point to that villain very easily. We know that person’s motivation.

I believe more than anything, it was everybody acting in their own self-interest, and the combination was devastating. The results were catastrophic.

Q: Do the people in the community in Mexico have any qualms about what has happened with opiates in the United States?

A: I do not know. … Those folks don’t have a lot of connection to America, even though they make money up here. …

I do know many small Mexican towns are very conservative, traditional places. … But also they’re very, very poor places, and if you find a way of getting beyond poverty, and you see everyone else doing it, and then after a while you begin to think, OK, well, that’s all right. I’m going to do this. That’s what happened in a lot of those areas. They say, you know what, I don’t see any other way to progress economically, and so this is going to be it.

Many of those guys were working in Mexico, but those jobs were dead-end jobs — sugar cane farmer, butcher, baker, construction worker. … And so this was clear that it was presented as an opportunity. More and more guys began to take it.

Pretty soon it became more of a culture; you were not cool otherwise. You didn’t have what girls wanted if you didn’t do it. You didn’t have land, a truck or money or nice clothes, you know, and you stood out.

Q: Very often when people are talking about helping addicts or changing sentencing laws, some people pop up and say, “Why didn’t you do this for crack cocaine? Why is everybody so concerned now about opioids when they didn’t care about us when we were addicted to coke?”

A: I would say it’s more complicated than that.

I covered crack cocaine in my first job, back in the late ’80s and early ’90s. With crack cocaine the problem — really, more than the drug — was the violence. There were drive-by shootings, carjackings, gangs — very scary. And it tended to blight neighborhoods. Most of them were black and, in California, a lot of Latino neighborhoods as well.

I don’t remember anybody of any race saying, “Oh, we should have more treatment for addicts.” That was not the point. The point was, “We’ve got to get this crime under control.” The crime was devastating.

I covered a case where shootout in an apartment severed the spine of a 3-year-old girl who was paralyzed for life. I still think about what ever became of her.

That was what came with crack cocaine. …. It was not just people getting addicted. Far more important than the addiction was the violence.

Q: Has there been any violence related to opioids?

A: That hasn’t happened. I do not believe for a second that anybody would be arguing for more treatment if we had this same record homicides, the same tremendous rise in crime that came with crack cocaine.

Q: The retail system for black tar heroin has been ingenious. Have other drugs been distributed that way?

A: I’m not aware of it. I think the only way you can do it is if you sell heroin, because heroin requires the addict to buy it every day. …. What they were, though, was the first to expand. Nobody expanded like these guys. Nobody said, it’s like a franchise, like we gotta to find new, virgin markets. … So we move on to Denver. From Denver we go from Salt Lake to Boise. From Omaha we go to DesMoines. And so on.

Q: Is there any part of the country that’s not touched now? When your book came out, there was a map with a few states …

A: They have stayed away from several states. I think they have stayed away from parts of the South. That doesn’t mean they will stay away forever.

But see … it’s very different now. There is no virgin market any more. Every place is a market, every place has lots of dealers. So it’s not like they can come in and find this sleepy heroin market, start selling it and pretty soon everyone else is just blown out because their heroin is much more potent and much cheaper and much more convenient to procure.

Nowadays, every place they go, they’re going to find lots and lots of competition. … They’re still operating, but they’re no longer the big fish in the small ponds that they were when they began to expand in ’99, 2000, 2001. There are many more people in Mexico getting involved, and many more people in the United States getting involved….

I talked to a guy in New York City, an heroin detective, and he said, “I would bet 70 percent of the Dominican cocaine dealers that we once were dealing with have now switched to selling heroin.”

Q: So now there’s this huge market for Narcan, or naloxone. Does that just perpetuate the epidemic by letting people go on and on, or is it a lifesaver?

A: If you don’t use Narcan, then you’ve just got to get used to going to a lot of funerals. People die. The problem is, up ’til now, we’ve used Narcan without using it as an opportunity. You revive somebody; I think it’s foolhardy to let them just go on their way. …

My feeling is that Narcan needs to be used in tandem with other things. …

It’s much better to view it as an opportunity, a chance to nudge or push this guy into treatment. Now is the time to push that person along elsewhere, nudge them in a different direction. It doesn’t mean it always works.

I was in Canton, Ohio, and a cop told me, “You know, the other day, … this women OD’d on the midnight shift, and the guys on the midnight shift revived her, took her to the ER, she leaves there. Shoots up again. The guys on the daytime shift revive her. Then, the swing shift, which is my shift, we find her dead.”

Q: That happens so much.

A: Exactly. If you don’t view Narcan as an opportunity to push the person into some other way, what you’re actually doing is setting yourself up to be an endless dispenser of naloxone. … No county can afford that. After a while, you will lose all political support for treatment and dealing in a more humane way with addicts if you don’t do this. …

People go, “Why are we spending so much money on these people who have just this death wish?” That’s the argument a lot of people make. You can kind of understand their point of view. There needs to be another way to deal with a Narcan-revived addict than simply letting them go on their way.

Q: I’m not sure there are enough treatment facilities for all the addicts we have, even for just the people who overdose.

A: I know. That’s why one of the important things I think we need to do about this is understand how it’s important to have a new way of running jail.

… Kentucky has a bunch of these, jails where they’re now using pods of the jail as full-time drug rehab clinics. From the moment you get up in the morning, you make your bed military-style, to the moment when you go to bed at night, you are working on your recovery — classes, NA meetings, physical exercise, prayer and meditation.

All the kinds things you would have in a rehab center on the outside, but you can’t afford it, you don’t have insurance to pay for it, you get in jail. I think that’s one of the big changes that needs to be considered.

Jail is just waiting to be redone. … People get stressed out, they get out of jail and run right back to the dope guy’s house. …

What this does require, though, is a change in our way of thinking — our political will, basically. Up to now, we’ve just said, Oh, just throw them away.

Q: In places where this has worked, how did they bring the sheriff along, or whoever is in charge of the jail?

A: The sheriff was the one who did it, or the jailer. I’ve met several sheriffs who have done this already. They’re like, “I can’t continue to do this the way we’ve always been doing it.”

I don’t know what it’s like in North Carolina, but in many other parts of the country, it’s been law enforcement that’s been the most innovative. A lot of the best ideas have come from law enforcement — very different ideas than maybe you would have expected from them. …

People don’t line up to say, “Please build a treatment center in my neighborhood.” It would cost a lot of money; they take a long time to build, they’re politically difficult to site. So where are we going to find more treatment space? Well, jail. But you gotta rethink jail. It’s not jail the old way. It’s a very, very different thing.

It’s a very nurturing environment. I never thought I’d use “nurturing” to describe a jail.

Q: In places where this has worked, have they worked in conjunction with a mental health agency or did they bring on staff who are experts?

A: They hire people to run it in the jail; it’s not always correctional officers. In one jail I know of, it’s a recovering addict who has a master’s degree in social work.

To me, this is one thing that can come out of this epidemic. We need to use jail as an asset, not a liability. It’s been an anchor around our neck.

Q: Are there other examples of different things law enforcement has done?

A: I would say the whole idea of not arresting addicts but funneling them to treatment, like the Angel program in Massachusetts. You’re seeing different attitudes with regards to the nature of policing. Now cops are working more closely with public health nurses and public health workers, for example. …

Mainly it’s a willingness among police officers to say, “Let’s try something else.”

They’re seeing the damage that this can do.

I think also they’re learning from crack cocaine … We gotta be deeply involved in our communities, extend a hand and become a team. Law enforcement is a real leader in all this.

Q: Any predictions about when this epidemic will run itself out?

A: I can understand why it happened. How it will run itself out, how long that will take and what the solution is, is a difficult thing.

I feel certain, though, that there is no solution. There are solutions. It’s not one thing that will do this. It’s many, many things. That’s why the whole community approach that you’re seeing in law enforcement and public health and many other groups combine… all of that seems like the right direction. That’s my very strong hunch.