David Shribman: In 1968, the world turned upside down

Published 12:55 am Sunday, March 11, 2018

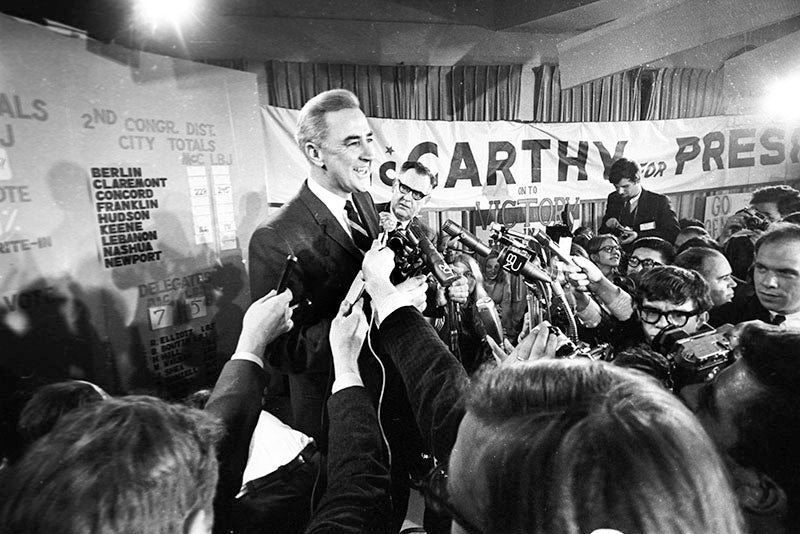

- Sen. Eugene McCarthy, D-Minn., is shown in this March 12, 1968 photo as he talks to campaign workers and the press at his Bedford, N.H. campaign headquarters. (AP Photo)

LONDONDERRY, New Hampshire — Of all the significant events that occurred in the landmark year of tumult and disruption of 1968 — when the Tet Offensive altered the dynamic of the war in Vietnam, when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated, when American cities burst into flames, when violence marred the Democratic National Convention — there were only three uplifting moments.

One was the midsummer mastery of pitchers Denny McLain and Bob Gibson, two men whose teams were destined to meet in an unforgettable World Series. One was the year-end Christmastime wonder of astronauts circling the moon, rendering the opening verses of Genesis into an American anthem of hope.

And the third — the least-remembered event of a much-remembered year — was the mobilization of young people here in New Hampshire who substituted their anger for activism and their impatience for inspiration. A half-century ago Monday, their determination to change the trajectory of American involvement in Vietnam also changed the course of presidential politics.

“It was a hugely important experience for everyone there our age,” said Alison Teal, who began the year working to deliver the Republican presidential nomination to Gov. George Romney of Michigan, only to join the McCarthy forces in late February. “We saw it as the beginning of something powerful.”

Rebellious year

All year long, there will be 50-year commemorations of the global upheavals that made 1968 the most rebellious year since 1917, perhaps since 1848. The world will mark the anniversaries of protests and strikes in France, the demonstrations against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, the mass protests in Germany and Brazil, and the beginning of terrorism in Northern Ireland.

But nowhere has anyone paused to recall what happened here on March 12, 1968 — when Lyndon Johnson won the New Hampshire primary but lost the will to run for re-election; when Eugene McCarthy startled the political world with a strong second and emerged as a serious symbol of the anti-war movement, even as his prospects for winning the nomination faded; and when Kennedy began to assemble a national campaign that would give life to liberal hopes but end his own life.

The youthful protesters who set all this in motion hit the streets of Manchester, Keene and Claremont in a far different way than their colleagues would do in Paris, Bonn, Prague and Chicago. Their street work would be a door-to-door mobilization for McCarthy, a reluctant warrior but perhaps the most ardent anti-war figure in establishment politics. From Wesleyan and Yale in Connecticut to Tufts and Harvard in Massachusetts to the University of New Hampshire and to Dartmouth way up in the state’s Upper Valley, these young people got “clean for Gene,” shearing and shaving to look more presentable — in truth, less threatening — to the burghers and homemakers of Bedford, Center Harbor, Franconia and Epsom.

The result was stunning. “What is happening,” the political columnist Mary McGrory wrote, “is that violet-eyed damsels from Smith are pinning McCarthy buttons on tattooed mill-workers, and Ph.D.s from Cornell, shaven and shorn for world peace, are deferentially bowing to middle-aged Manchester housewives and importuning them to consider a change of commander in chief.”

Youthful activism

It is hard to determine who was changed more by this insurgency: the insurgents or those facing this unlikely surge of political activism.

“For many of us this was a turning point,” said Robert H. Ross, a Dartmouth student who became a United Church of Christ minister. “I’m startled now by how optimistic we were. We thought we were on the threshold of a ‘change-the-world’ movement for a cultural shift, a greater social justice and world peace.”

Among the principals in the movement were Gerry Studds, who would later serve 24 years in Congress; Curtis Gans, co-founder of the influential Center for the Study of the American Electorate; and Sam Brown, who would later organize the two anti-war moratoriums, serve as treasurer of Colorado and run the country’s VISTA and Peace Corps operations for Jimmy Carter.

“Those last weeks it became a phenomenon,” said Brown. “We were in a situation of figuring out not to have too many people in the state rather than needing to find more.”

Because while the brainpower came from that inner circle, the horsepower came from the students.

Youth uprising

“This was basically a youth uprising in New Hampshire,” said Richard Olson, a retired United Auto Workers publications editor who as a youth was a Republican and who as a Dartmouth student drifted into the radical Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). “It was the result of a lot of struggle about how to do something about the war that was more than protesting the war.”

Richard Parker, a co-founder of Mother Jones magazine who now is a lecturer in public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, said that some of the voters he met on the streets of Hanover and West Lebanon thought the McCarthy he was supporting was Sen. Joseph McCarthy, the Wisconsin Republican who lent his name to the anti-communist witch hunts of the 1950s.

“It was winter in New Hampshire, and it was cold,” Mr. Parker recalled. “You had your scarf on, you had your hood up, you were walking through sludge in your boots. But we felt we were doing something important in a period when Vietnam and segregation were blowing up the America I thought I was growing up in.”

Week after week the students arrived, and as the primary approached, the election chronicler Theodore H. White returned to New Hampshire to find that “the kids, those out-of-state students — they were having an effect.” He walked from the state Capitol in Concord down the hill to Pleasant Street and found an astonishing sight, a supremely sophisticated anti-Johnson effort:

“Suddenly, all that had been taught the bright young students of political science, children trained on computers and methodology, had leaped from classroom to reality. They knew what they were doing. They were skilled. They were organized. … And they were happy.”

Committed to change

Happy — and on the verge of lifelong commitments to political change. One of them was Robert B. Reich, the labor secretary in the Clinton administration who said the McCarthy campaign “marked the moment that an entire generation of college students — my generation — suddenly became serious about electoral politics.” He was not alone.

David M. Shribman is executive editor of the Post-Gazette (dshribman@post-gazette.com, 412-263-1890). Follow him on Twitter at ShribmanPG.