5 myths of gerrymandering

Published 12:00 am Sunday, March 11, 2018

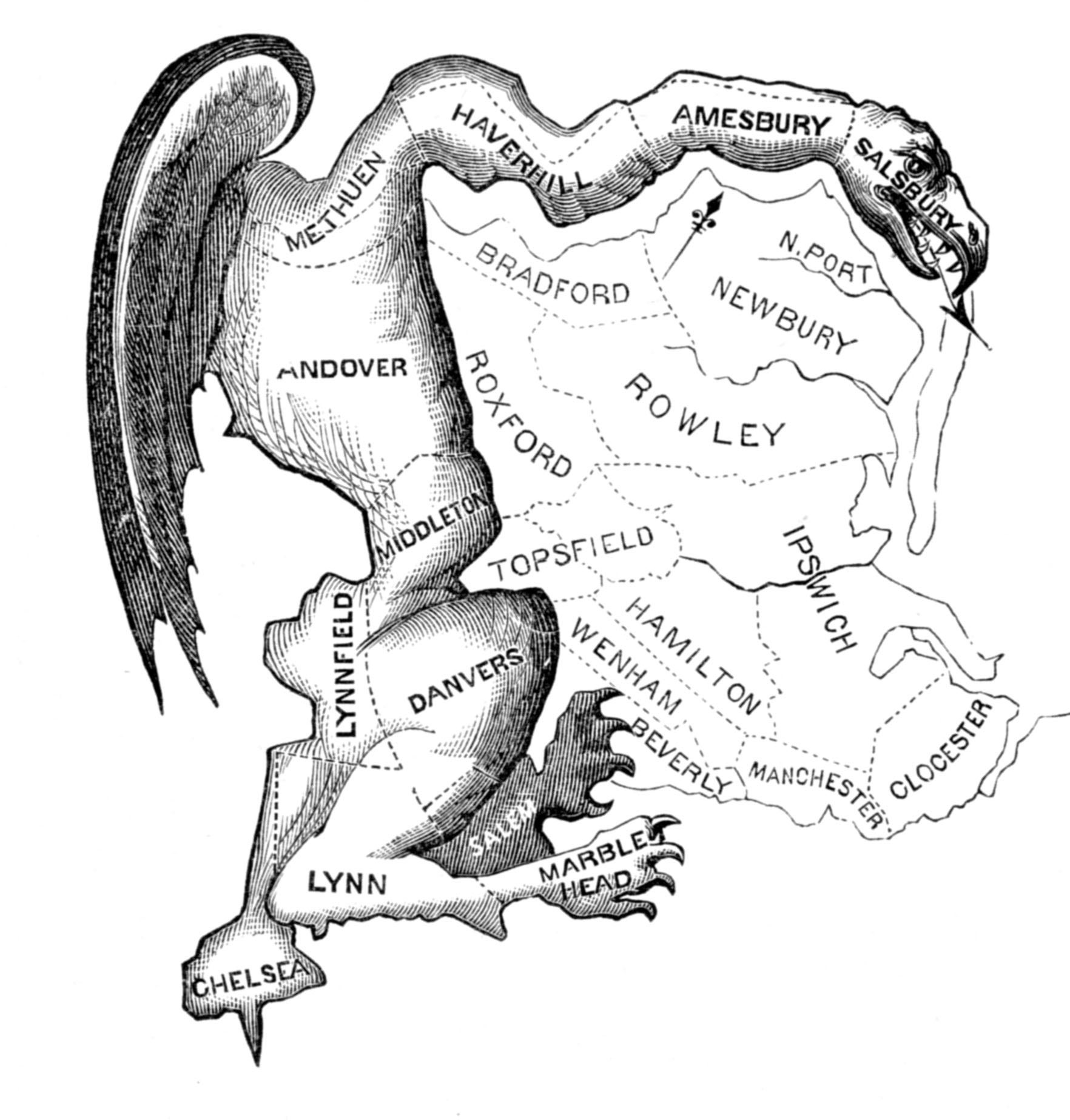

- "The Gerry-mander" first appeared in this cartoon-map in the Boston Gazette, 26 March 1812.

By Ari Berman

Special To The Washington Post

Gerrymandering — in which politicians manipulate electoral boundaries for partisan advantage — is emerging as a key issue in the midterm elections. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court recently redrew the state’s GOP-dominated congressional map, boosting Democratic chances of taking back the House of Representatives. The U.S. Supreme Court is weighing whether to outlaw gerrymandering and has three big cases on its docket this year from Wisconsin, Maryland and Texas. Gerrymandering has gone from a wonky technical problem to a matter of great political intrigue. Yet there are many misperceptions about how the process works.

Myth No. 1: Partisan gerrymandering is a long-accepted part of U.S. politics.

Practically every history of gerrymandering includes a reference to Massachusetts Gov.Elbridge Gerry, who in 1812 approved a state Senate district shaped like a salamander that became known as a “Gerry-Mander.” It’s a frequent talking point among politicians that gerrymandering is as old as American democracy itself. “It is well established that partisan intent in districting is lawful,” the state of Wisconsin argued when its new State Assembly map was challenged in court. “Districting is ‘inherently political’ and ‘there is nothing in the Constitution to prevent’ consideration of political factors,” the leaders of Pennsylvania’s legislature wrote in January.

These arguments ignore that America was founded on the basis of fair representation, as a reaction to the British system of “virtual representation” that gave Americans no say in the running of their colony. Gerrymandering has been denounced as long as it’s been practiced. Gerry himself called the map he signed “highly disagreeable,” and the Salem Gazette, which coined the term “gerrymander,” wrote that “this Law inflicted a grievous wound on the Constitution.”

Moreover, today’s gerrymandering — because of sophisticated technology, increased political polarization and the clustering of partisans in like-minded areas — makes the map signed by Gerry look quaint, according to a study by Nicholas Stephanopoulos of the University of Chicago and Eric McGhee of the Public Policy Institute of California. Simon Jackman of the University of Sydney analyzed 786 different state legislative plans between 1972 and 2014 and found that five of the 10 worst Republican gerrymanders had been passed since 2010.

Myth No. 2: GOP dominance has more to do with geography than gerrymandering.

In 2012, Democratic candidates for the U.S. House won 1.4 million more votes than Republicans did, but Republicans controlled 33 more seats.

“The Democrats’ loss in the House was caused largely not by gerrymandering, but districting itself,” argued Nicholas Goedert, a political scientist at Virginia Tech University, in the political science blog the Monkey Cage. Many experts have echoed this view. “Because liberals, young voters, minorities, and other members of the Democrats’ coalition tend to be concentrated in cities and/or placed into minority majority districts, this damaged their ability to win congressional districts,” wrote Sean Trende, the senior elections analyst for Real Clear Politics. Before the 2016 election, the New York Times ran an opinion piece titled “Go Midwest, Young Hipster,” examining Democrats’ clustering in urban or coastal areas.

Yet geography alone doesn’t explain Republican dominance in many states. Political geographers from Stanford and Carnegie Mellon found, for instance, that there was “less than a one in one thousand chance” that the map passed by Wisconsin Republicans, which gave them 60 percent of the seats in the State Assembly, was based on where Democrats lived. “The partisan asymmetry in the existing map,” they wrote, “… was carefully and deliberately created, not a result of the natural clustering of voters in Wisconsin.”

The same was true in Pennsylvania, where University of Michigan political scientist Jowei Chen discovered “a small geographic advantage for the Republicans, but it does not come close to explaining the extreme 13-5 Republican advantage” in the state’s congressional delegation. Indeed, Pennsylvania Republicans went to almost comic lengths to contort political boundaries for partisan advantage, drawing one district, nicknamed “Goofy Kicking Donald Duck,” that spanned five counties and 26 municipalities, and at one of its narrowest points ran through the parking lot of a seafood restaurant in the town of King of Prussia.

Myth No. 3: Gerrymandering doesn’t determine political outcomes.

Wisconsin Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, a Republican, said Democrats complain about the GOP’s sizable majority “because their candidates and their issues don’t appeal to the majority of Americans.” His legislative counterparts in Pennsylvania likewise argue that gerrymandering doesn’t determine political outcomes. “The only plausible reason it would be ‘harder’ for Petitioners to elect candidates of their choice,” wrote the leaders of Pennsylvania’s legislature, “is because it may be ‘harder’ for Petitioners to persuade a majority of the other 705,000+ voters in their districts to agree with them on the candidate they prefer.”

But across the country, both parties have secured airtight majorities for multiple election cycles by controlling the redistricting process. In 2012, Republican legislative candidates received 48.6 percent of the vote in Wisconsin but won 60 percent of the seats in the State Assembly. In 2014, Democratic candidates received 57 percent of the vote in Maryland but won 88 percent of the state’s congressional seats.

Indeed, both parties have been explicit about their partisan aims. Tad Ottman, a legislative aide who helped draw Wisconsin’s maps, told Republicans, “The maps we pass will determine who’s here 10 years from now.”

The GOP chairman of North Carolina’s House redistricting committee admitted: “We want to make clear that we … are going to use political data in drawing this map. It is to gain partisan advantage.” Former Maryland governor Martin O’Malley, a Democrat, said, “Part of my intent was to create a map that, all things being legal and equal, would, nonetheless, be more likely to elect more Democrats rather than less.” (Republicans had full control of the redistricting process in 21 states vs. eight states for Democrats after the 2010 elections.) As Karl Rove famously predicted before the 2010 midterms, “He who controls redistricting can control Congress.”

Myth No. 4: Courts have historically left redistricting to states.

After Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court drew a new congressional map, reducing the GOP’s big advantage, the state’s Republicans argued that the courts should stay out of redistricting matters. “The United States Constitution expressly delegates districting authority to state legislatures,” wrote legislative leaders.

During oral arguments over Wisconsin’s legislative map in October, Justice Neil Gorsuch made a similar point: “Where exactly do we get authority to revise state legislative lines?”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had the answer: “Where did one-person/one-vote come from?”

The courts that interpret the Constitution have long overseen the process of drawing district maps. In the 1930s and 1940s, legislative districts were wildly unequal in population; some had 900,000 people, others as few as 10,000. That gave certain voters a much bigger say than others in deciding who was elected.

At first, the Supreme Court refused to touch the issue. But in 1962, Justice William Brennan wrote for the majority in Baker v. Carr that “judicial standards under the Equal Protection Clause are well developed and familiar, and it has been open to courts since the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment.” That led to the “one person, one vote” cases of the 1960s, which mandated that districts be roughly equal in population and, as a consequence, more fair. The Supreme Court has the same power to strike down partisan gerrymandering today.

Myth No. 5: There are no standards for gerrymandering.

“Gerrymandering is distasteful,” said Justice Samuel Alito during the Wisconsin arguments. “But if we are going to impose a standard on the courts, it has to be something that’s manageable, and it has to be something that’s sufficiently concrete.”

Chief Justice John Roberts dismissed the social science used to identify gerrymandering as “sociological gobbledygook.” This is not a new concern for the justices: In the 2004 case Vieth v. Jubelirer, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote, “There are yet no agreed upon substantive principles of fairness in districting.”

But political scientists have developed a number of concrete tests to measure partisan gerrymandering, such as the number of “wasted” votes for a party (as when Democrats are submerged in a deeply Republican district) or when a party receives far more seats than its share of votes.

At the Wisconsin argument, Justice Stephen Breyer laid out a workable standard for the court: Were the maps drawn by one party? Do they unfairly benefit one party over the other? Does that partisan advantage last over a series of election cycles? And, if so, was there any good reason for the map other than achieving partisan control? “I suspect that’s manageable,” he said.

Berman,a senior reporter at Mother Jones, is author of “Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America.”