Ote Corriher provided a Landis connection to the Civil Air Patrol

Published 12:05 am Saturday, December 16, 2017

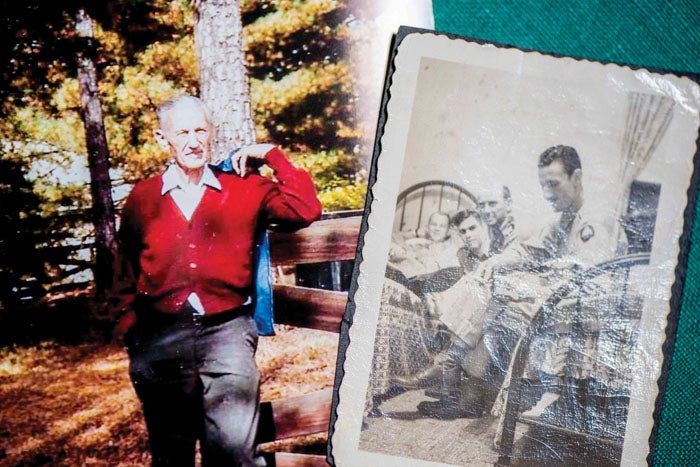

- Landis' Otho Corriher was one of many North Carolina pilots that performed civilian duties to support the war effort during World War II. Jon C. Lakey/Salisbury Post

Museum at the Manteo Airport honors his service

By David Freeze

For the Salisbury Post

It didn’t take Otho Corriher, called Ote by nearly everyone, long to figure out that he wanted to be a pilot. When World War ll started, Corriher wanted to do his part. He applied and was accepted into the Civil Air Patrol, a fledgling organization just six days older than the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor.

A historical marker near the Manteo Airport says simply, “Coastal Patrol Base, first in N.C., opened ½ mile S.E. in 1942. Civilian pilots supported military and patrolled for German U-boats.”

The coast off the Outer Banks had become the most dangerous area for shipping in America just after the start of World War II, with U-boats finding unchallenged success at sinking and damaging vital ships. The area became known as Torpedo Junction and, with the war ramping up, little military equipment was available to defend the coast.

The Civil Air Patrol was seen as a way to use America’s civilian aviation resources to aid the war effort. Pilots and small aircraft owners applied to join the organization, loosely assigned to and regulated by the Army Air Force.

That first base at Manteo became the home of Corriher and several friends including Clay Swaim, longtime manager of the Rowan County Airport. They joined about 100,000 others nationwide, providing America’s first line of defense of coastal areas.

Corriher, a flight enthusiast, arrived at Manteo in 1942 to join the “Flying Minutemen.” Volunteer aviators, often using their own planes, conducted sea rescues, towed targets for military training, performed courier service and even fought forest fires.

The pilots, mechanics and administrators out of Manteo and nearby Beaufort took to the air in small and often underpowered planes searching for German submarines and sailors in distress.

During January 1942, at least 19 U-boats were operating along the coast. By 1943, the North Carolina Civil Air Patrol numbered 1,100 members and 14 squadrons.

Before the establishment of the Air Patrol bases, 78 vessels were sunk and 18 damaged. Only two ships were torpedoed during the time of base operations. The Navy took over coastal patrols in 1943.

Born in 1909, Otho Corriher was an adventurer of sorts, having driven a remodeled 1927 Ford at the age of 18 on a 1,500-mile jaunt that included visits to Texas and New York.

The exploits of Charles Lindbergh inspired lots of young men to become pilots, including Corriher, who received his flight training from Swaim. What followed was the family’s Landis Airport, according to friend and historian John Allen.

“Ote learned to fly in a Curtis Jenny in 1930,” Allen said. “Lotan Corriher, his dad, didn’t want Ote in airplanes. But he did offer later to build a better and longer airstrip near today’s Corriher Mill softball field.”

Allen added, “Corriher and wife Sadie would sometimes roll out their Waco 10 airplane and go fly on nights with a full moon to Charlotte to see the lights and then return home, landing on the dark 900-foot runway. He didn’t need lights on his plane because there seldom were other planes in the sky.”

After signing on with the CAP, Corriher left behind the family textile mill business for more adventure.

Daughter Marianne Wilson, who with her husband, David, lives near the original site of the airport, shared the story. “They had no barracks and they had to live in a rented home,” she said. “I remember that my mother and I went to visit him during Christmas 1942. We took along a friend whose dad was also a CAP pilot. When we arrived, his dad and another man had not returned from a flight over the ocean and were considered missing. They were later found dead, I think the only two personnel lost out of that base.”

Corriher served from July 27, 1942, until May 27, 1943. A flight record shows four airplanes, including one piloted by Corriher, flew a search mission on Feb. 7, 1943. Each plane included the pilot and an observer. Corriher was listed as one of 13 pilots available at the time.

When his tour ended, Corriher was 34 and a lieutenant. A monument in front of the airport bears his name.

In an interesting side note, nearly all of the planes used by CAP were light pleasure planes, according to Allen.

“The submarines were inefficient when under the sea, so they often stayed on the surface whenever possible,” Allen said. “Sighting a CAP plane would make them submerge because the plane could radio the location to the military. Sometimes the plane would fly off in the distance, wait for the sub to surface and then go back toward it.”

The light planes were not armed at first but later carried a rifle or dropped a small bomb out the window. Later CAP planes had a small bomb mounted underneath, and legend has it that at least two subs were struck by those bombs.

A painting in the Manteo CAP Museum shows a small Cub plane banking up and away from a bomb explosion on the deck of a U-boat.

Congress awarded the Civil Air Patrol the Congressional Gold Medal in 2014 in recognition of its members’ contributions during the war. They came from all walks of life, including a world-famous pianist, a sitting governor, a storied Wall Street financier, a pioneering African-American woman aviator, future Tuskegee Airmen, the head of a major brewery and the founder of the Krispy-Kreme chain. The doughnut founder, Vernon Rudolph, also served in Manteo.

Ote Corriher followed his Civil Air Patrol service with three years in the Army. At war’s end, he wasn’t excited about coming home to his job as the treasurer of the family mill business, but he did. His interest in the Landis Airport remained.

Allen said the airport flourished until the early 1960s.

“They went to Camden and bought used military planes after the war and made them into crop dusters,” he said. “They also built planes in the basement of Corriher’s house. Cub planes were painted yellow and all the upstairs furniture eventually had a yellow sheen to it.”

Allen said Corriher’s interest turned to restoring classic cars. “His collection was considered world-class,” Allen said.

A restored State Highway Patrol car garnered “Honorary Patrolman” for Corriher, and his 1941 Indy-winning Miller Racer remains on display at Indianapolis Raceway Museum, according to “Hanger Sweepings,” a book by Harold Mills. The family sold the mill in the early 1970s.

“My dad was considered a quiet man,” Wilson said. “He was the sweetest person, and I loved him dearly. He didn’t especially enjoy traveling after the war, unless it was for a purpose. Dad died at 82 and he never flew again, not even on a commercial flight, after the war. But he helped everybody. We found letters from friends, his workers and churches after he died thanking him for his help and we never knew anything about it.”

Allen added, “And he was the image of the perfect Southern gentleman.”

“The Highway Patrol led his funeral procession and a patrolman was at every intersection, standing at attention and saluting,” Mills said.