The unknown volunteer: World War I vet Pat McCora lived a life full of intrigue

Published 12:00 am Saturday, November 11, 2017

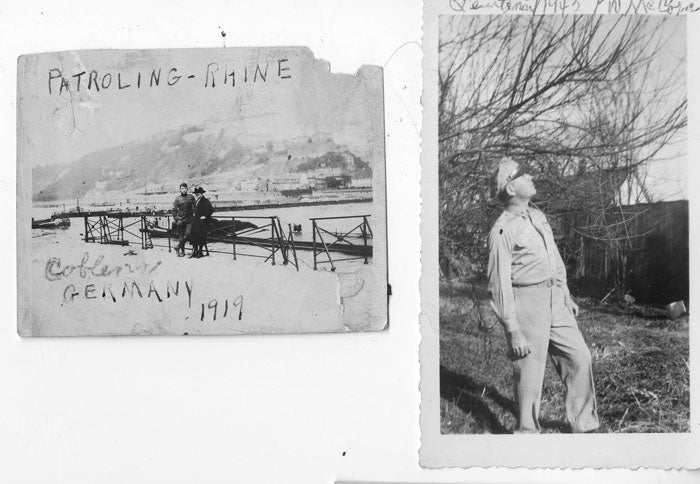

- Clockwise from top left: Pat McCora with his first wife in Coblenz, Germany, in 1919; McCora looks skyward as part of the Civil Air Patrol in Rowan County during World War II; McCord sported a beard during Rowan County's Bicentennial in 1953; McCora, left, boxes a German prisoner in Sandberg, Germany, in June 1920. Submitted photos

SALISBURY — Stuck in the bowels of the History Room at Rowan Public Library are two books written by the late P.W. “Pat” McCora Jr.

But you won’t find them under that name. “The Unknown Volunteer,” published in 1937, was written by Daly Wise. A softbound “The Enemy Died in Her Arms,” from 1975, was penned by Bill McCora.

The fact that Pat McCora resisted attaching his real name to either novel hints at his long-held fear that the Army would somehow discover the truth — that he had fought in World War I under a fake name.

Meanwhile, his 49-year-old grandson, Thomas McCora, has come to believe that much of the supposedly fictional story Pat tells in each of those novels is close to what his grandfather actually experienced in the Great War.

It’s a narrative full of espionage, romance and even a German firing squad. Thomas McCora says he would put “my last dollar on it” that the novels are more fact than fiction.

McCora and his 24-year-old son, Caleb, who is studying for his master’s in education at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, are trying to assemble their own book, which they hope can be ready by Nov. 11, 2018, the 100th anniversary of the first Armistice Day (Veterans Day).

Thomas McCora said the working title is “Doughboy: The True Story of an Unknown Volunteer,” and it’s a look at the interesting life of his grandfather, who died on Veterans Day 1993.

•••

Pat McCora’s first book under the pen name Daly Wise did not go unnoticed, at least locally.

The Salisbury Evening Post reported that the book’s publisher, Meador Publishing Co. of Boston, described the novel as “a war story in a New Vein; filled with action, romance and excitement, on land and sea and in the air.”

Post Editor Spencer Murphy reviewed the book. On one hand, he was kind in describing McCora as “a matter-of-fact and likable employee of the Southern Railway office here and a war veteran with a rich treasury of experiences from across the water.”

But Murphy also was a tough critic. He said McCora told a genuinely interesting story with credible narrative in spots, but added it was “poorly balanced in proportion and handicapped by an outmoded style of writing.”

Murphy said the most convincing and effective parts of the novel were his descriptions of scenes from the front, but he also expressed hope “that in his second novel, he’ll shed overworked trite phrases and his pomposity in dialogue.”

Thomas McCora says the much later second novel published by Town House Press in New York tells essentially the same story as “The Unknown Volunteer.”

“It’s not a bad story,” McCora says in his own critical review of his grandfather’s work. He says Pat McCora used words of his era in an attempt to make it more authentic. He also kept it simple, so anyone could understand.

“This is not all he experienced,” McCora says. “This is just the softer side of it.”

Between books, Thomas says, his grandfather wrote several hundred articles for a faith-based publication called “Our Daily Bread.”

•••

Toward the end of Pat McCora’s life, Thomas McCora spent a lot of time with his grandfather, caring for him and helping him enroll for veterans benefits.

Because he had used a fake name — Paddy Pecora — when he enlisted for World War I in 1917, Pat McCora had never sought VA benefits until the end of his life. Even after all those years and despite his two Purple Hearts, Pat feared he could still be imprisoned for using the fictitious name as a soldier.

In 1992, Pat McCora fell and broke a hip. He had the joint replaced and went through his initial rehabilitation at a nursing home, but his wife, Annie, couldn’t cover the cost of home health care. It was then Thomas McCora, a nurse by training, started the process of trying to get his grandfather VA benefits.

Thomas McCora talked to a man named Bill Earnhardt at the Salisbury VA, who told him to bring him a Xerox photocopy of the medals his grandfather had received, photographs he had taken in Europe — anything to prove he had served.

The Army eventually verified that Pat McCora and Paddy Pecora were one and the same. There were no repercussions, and he even received a certificate of recognition for his service from President Bill Clinton.

At the time, there were just fewer than 2,000 surviving U.S. soldiers from World War I. Pat McCora stayed at the Salisbury VA hospital for less than six months before his death in 1993.

Thomas McCora had long conversations with his grandfather about his war years and the books he had written. Thomas has spent many of the years since Pat’s death trying to track down facts and see if they coincide with the notes he took of their conversations.

“I pried it out of him,” Thomas McCora says. “I told him, ‘I want to know. I want to know these things.'”

•••

P.W. “Pat” McCora was born in 1898 in Reinfro, Canada. His dad, a fairly wealthy immigrant from Ireland, first settled in Canada before moving his family to New York City. He became a co-owner and manager of hotels.

Pat McCora grew up in Manhattan around Battery Park. His mother died in 1907 , when he was 9, and he had a troubled relationship with his father, especially after his dad married the family’s nanny — a controversial development.

“You were not supposed to marry the help in those days,” Thomas says.

An increasingly rebellious Pat McCora often would sneak off from the household, wander the streets and be delinquent from school. Thomas says Pat McCora told him he had loved airplanes from their earliest invention and a desire to fly drew him toward military service.

Knowing his father would not approve, Pat McCora ran off to Canada and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force when he was 15 or 16. But his father had him sent home because of his age.

Later, the young McCora left home again and joined the Army to fight in the Mexican border war against Pancho Villa. Thomas McCora says Pat was wounded in that fighting and received a Purple Heart. Again, his father put an end to Pat’s military career and told his son he would be going to college instead.

Pat McCora enrolled at Lehigh College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and served as a chauffeur for an aunt who lived there. He attended school for a year before the United States was drawn into World War I.

McCora enlisted in the Army in June 1917 and had 90 days to report, which he did in September. He enlisted under the name Paddy Pecora, no doubt a way to keep his father from finding out. He also gave the Army his wrong birthdate by three years to make himself older. He wrote July 7, 1895, on the registration form, although he had been born on that date in 1898.

McCora was off to basic training, where a fellow soldier happened to be from Spencer, North Carolina. Before they shipped out for overseas, the guys visited Spencer together, and the friend’s father, who was a yardmaster for the railroad, told McCora if he needed a job after the war, he would find something for Pat in the rail yard.

“That was in the back of his mind before he left,” Thomas McCora says.

During the war, McCora served with the 3rd Army Infantry, 7th Machine Gun Battalion, and saw action in France, Belgium and Germany.

Thomas says his grandfather fought in seven significant battles and volunteered every time for the most dangerous assignments. He also became a boxer in the Army and was undefeated in his weight class, Thomas McCora says.

Pat McCora received a second Purple Heart after taking shrapnel to his leg from a grenade blast. He would fight in Europe through Armistice Day on Nov. 11, 1918, and stay in the Army (and Europe) until Oct. 26, 1920.

But there was more to his war story — a woman, who by the second McCora book was identified as Frances. Thomas McCora says Frances really existed and, in fact, married his grandfather in Germany before being killed overseas in an accident.

Frances was a daughter of a couple who worked at one of his father’s motels.

In Pat McCora’s books — and Thomas thinks this really was the case in real life — Frances was determined to prove her love to the young soldier (Pat), and she became a Red Cross nurse in hopes she could follow him to Europe.

At the time, a lot of German spies were operating in New York, and one of them was a woman who died in an automobile crash. Frances came across her bag after the accident and discovered a lot of important-looking documents in German.

Frances was bilingual and assumed the identity of the German spy, in hopes of expediting her passage to Europe.

“She went through a lot,” Thomas McCora said. “He (Pat McCora) did confirm that she did that.”

In the McCora books, Frances came to know a German officer for whom she had cared as a nurse. It was that relationship that saved her from a German firing squad after her true identity as an American was exposed.

Thomas McCora says his grandfather married Frances in Europe, and he has a grainy photograph of them standing near the Rhine River in Germany.

•••

After World War I, Pat McCora remembered the promise of a possible job in Spencer and settled here, starting out at Spencer Shops as a fireman and helping in the Roundhouse.

Later, he became a clerk in the Spencer Shops office, basically working in payroll and handing out paychecks. He also coached and pitched for the softball team.

Pat and his wife, Annie, married in 1925. They would have two sons and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Pat McCora would work for Southern Railway 43 years before retiring in 1965.

When he wrote “The Unknown Volunteer” in 1937, Pat gave many of his fictional character names of his friends in Salisbury, including Ross Sigmon, J.P. Mattox and B.W. Arey.

But a more important name was Harry Edwin, a soldier friend of Pat’s who died in the war. Pat and Annie named one of their sons Harry Edwin McCora in tribute to him. Harry was Thomas’ dad.

As far as Thomas McCora knows, Pat McCora never told his wife, Annie, he had been married briefly to a girl named Frances in Germany.

Pat McCora involved himself in many things.

During World War II, he served as a lieutenant for the Civil Air Patrol in Rowan County.

He once secured a patent for a shaving brush that dispensed foam from its handle. He composed and had copyrights on several songs, for which Thomas still has the sheet music.

He wrote poems and constantly carried a notebook to write down some of his thoughts. He owned an antique clock shop and managed, for a time, the Salisbury Skeet Club and Restaurant.

Pat McCora also took long walks, Monday through Saturday, from his home in Forest Hills until he broke his hip in 1992. He was a charter member of Maranatha Bible Church.

His newspaper obituary in 1993 never mentioned the books he had written and certainly nothing about a lost wife in Germany.

Pat McCora is buried in Rowan Memorial Park. Among all the medals, poems, music and documents he left with Thomas McCora, there is a slip of paper with the epitaph he wanted etched on his tombstone.

It was to the point, like his novels:

“As I am today

So you will be

Prepare to meet God

and follow me.”

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263 or mark.wineka@salisburypost.com.