What’s next, ‘Young Jane Young’?

Published 12:00 am Sunday, August 27, 2017

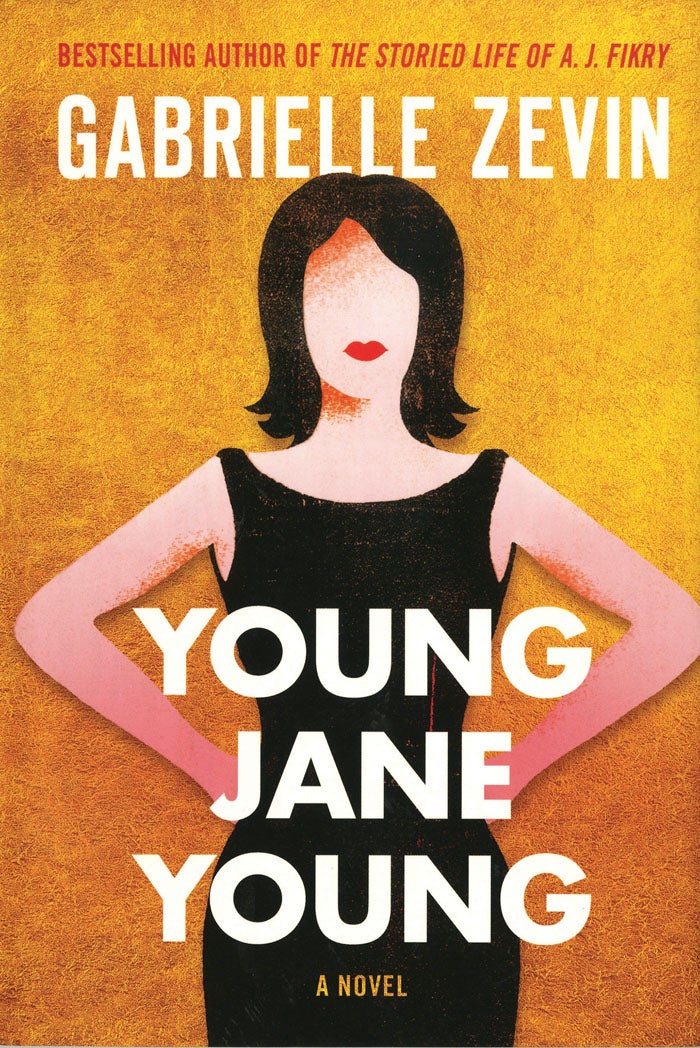

“Young Jane Young,” by Gabrielle Zevin. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. 2017. 294 pp.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

Gabrielle Zevin’s timing is perfect.

Just as we seem to be constantly on the verge of political scandal — and we’ve had no lack lately — she comes up with “Young Jane Young.”

The cover of the book, a faceless woman with bright red lipstick and a little black dress, hints at what’s inside.

This is the story of a young woman ruined by a political scandal who won’t just shrivel up and blow away. Nor will she play the victim and use the story to become, even momentarily, famous.

She changes her name, moves 1,000 miles away from her old life and completely starts over. But she manages it, with some confidence born of her “who cares what happened in the past” attitude. She has a child to take care of and she has to find success that is not tainted by what she did at 20, when she was young, lusty and naive.

Zevin, author of the sweet little heartbreaker “The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry,” and novels for young adults, has the chutzpah (a good Yiddish word) to make her fallen heroine someone you can cheer for.

After all, it takes two to tango. Young Aviva Grossman gets an internship with a likable, handsome congressman, Aaron Levin, and falls for him almost immediately. She pursues him, but he, older, presumably wiser, should have stopped her. He and his wife, Embeth, used to live in the same exclusive development Aviva grew up in.

Now she’s a young adult, busty, hard to resist. She’s smart, quick to find answers and to introduce the congressman’s staff to that emerging marvel, social media back in its fledgling days.

Zevin deftly lets different women tell the story, starting with Aviva’s funny, forthright mother, Rachael Grossman, now 64 and guileless, looking back at moving forward. Rachael, now divorced, is trying online dating.

Rachel’s description of young Aaron Levin is striking. Then he was a “lowly state senator” and his wife, Embeth, earned more money as counsel for a group of hospitals. Levin is “six foot two inches tall in New Balances, with black curly hair and blue-green eyes and a big, kind, dopey smile. The man could wear a dress shirt.”

Jewish Rachel’s frequent use of Yiddish terms adds to her character. The sound of some of the words is so descriptive, particularly of unpleasant things. She can get by with a lot this way

Rachel is charming in a disarming way, and, like her daughter, very direct. She’s a bad liar, which gets her into trouble as she tries to extricate her daughter from her disastrous relationship before it’s too late — and then it IS too late.

Rachel should have her own book some day.

Then Jane Young tells her story, making a passing reference to Aviva Grossman, the Monica Lewinsky of south Florida. Jane is a wedding planner, a single mother and a happy-ish resident of a small town in Maine.

Franny, a bride with her own set of very special problems, befriends Jane as they plan the girl’s wedding to a snobby, arrogant real estate agent. Jane does not seek this friendship, but she knows a lost puppy when she sees one.

Next come the remarkable insights of Ruby, Jane’s precocious and therefore misfit daughter. Ruby tells her life story in emails to her pen pal in Indonesia, using enough quotation marks to fill a wedding venue.

Ruby is much more comfortable around adults. You have to love her alarming maturity and fitting childishness.

At this point, Zevin shows us the toxic world of Embeth Levin, the congressman’s long suffering wife. She has given up everything to become a “political wife,” the one in the background, the one attending fund-raisers and making connections and smiling at strangers and shaking hands and filling in when Levin is too busy to leave Washington.

Treatments for breast cancer leave her drained and have turned her into a gray woman who can still put on the political wife’s face and clothes and go out for the good of the cause, but she suffers alone.

Embeth has never been a happy woman, but a driven one. She still hates Aviva Grossman. It’s easy to feel sorry for her, but to also dislike the cold-bloodedness of her attitude.

And now, we hear from Jane again, who’s telling the story of Aviva Grossman, bit by bit, through diary entries. The diary is in the form of a Create-an-Adventure book.

After each entry, Jane presents an option: “If you continue seeing him, turn to page 86.

“If you tell him it’s over, turn to page 150.”

Aviva always makes the unfortunate choice. And to compound matters, she writes a blog about the relationship, though she never reveals names.

It’s that smoldering pile of Internet indiscretion that haunts Aviva to this day. Though the story is by now an old one, it’s easy to find.

Finally, we learn Jane Young’s plans for the future, and it’s big, really big. How can she hope to overcome the slut-shaming America is so fond of? How can she even lift her head to the glare?

The question Zevin handles so deftly is, how can she not? She owes it to herself and her daughter to pull up her boots, step in the mud and walk right through it. She’s got the guts. And a big heart she’s somehow forged out of cynicism.

Zevin wags her finger at a society obsessed with appearances and indiscretions, one that puts all the blame on women. And she comes up with just the right ending.