Join the discussion of ‘Blood Done Sign My Name’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, August 13, 2017

- Mike Wiley brings to life the recollections of author Tim Tyson.

Staff report

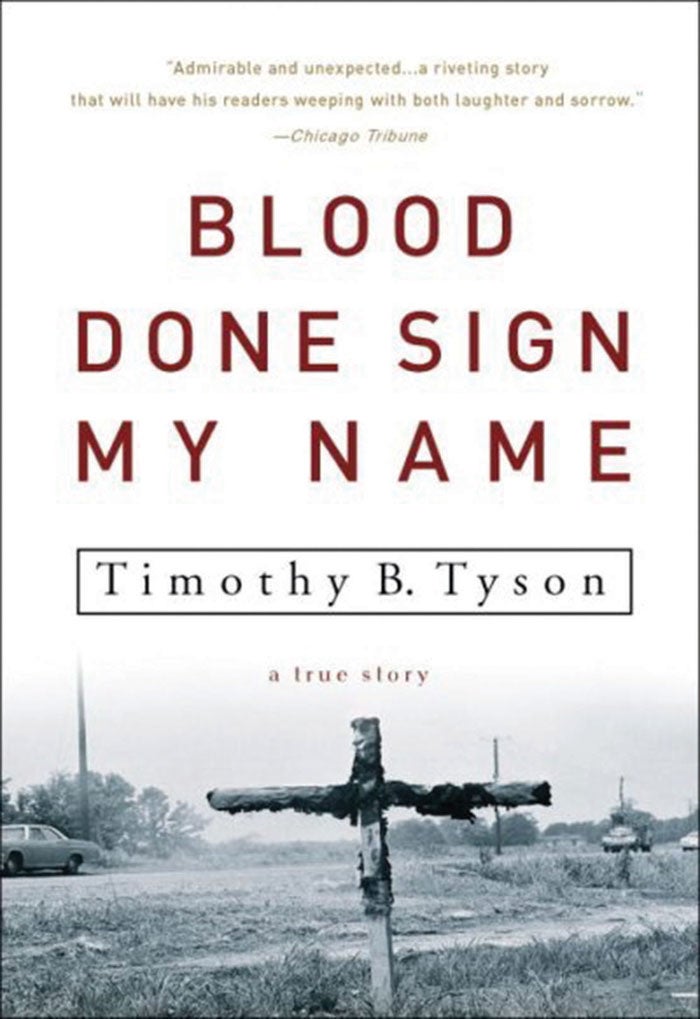

For the third and final book in the 2017 Summer Reading Challenge, we will discuss Timothy B. Tyson’s acclaimed “Blood Done Sign My Name.”

Tyson presents the facts of a brutal murder in his hometown of Oxford, N.C., when he was 10 years old.

The murder had a lasting effect on Tyson’s life, and his study of the incident and subsequent career as a professor of African-American Studies shows his commitment to telling the truth.

The truth is not always easy, and “Blood Done Sign My Name” is full of racial tensions, ignorance, anger and consequences.

Dr. Ken Walden, director of United Methodist studies at Hood Theological Seminary, will discuss the book and its relevance to our times on Tuesday, Aug. 15, 7 p.m. at the Hurley Room at Rowan Public Library.

On May 11, 1970, Henry Marrow, a 23-year-old black veteran, walked into a crossroads store in Oxford owned by Robert Teel and came out running. Teel and two of his sons chased and beat Marrow, then killed him in public as he pleaded for his life.

Tyson heard one of his boyhood friends blurt out the words that were to forever change his life: “Daddy and Roger and ’em shot ’em a nigger!”

The cold-blooded street murder of Marrow by an ambitious, hot-tempered local businessman and his kin in the spring of 1970 would quickly fan the long-flickering flames of racial discord in the proud, insular tobacco town into explosions of rage and street violence.

Like many small Southern towns, Oxford had barely been touched by the civil rights movement. While lawyers battled in the courthouse, the Klan raged in the shadows and black Vietnam veterans torched the town’s tobacco warehouses.

Tyson’s father, the pastor of Oxford’s all-white Methodist church, urged the town to come to terms with its bloody racial history. In the end, however, the Tyson family was forced to move away.

The details are often chilling: Oxford simply closed its public recreation facilities rather than integrate them; Marrow’s accused murderers were publicly condemned, yet acquitted; the town’s newspaper records of the events — and indeed the author’s later account for his graduate thesis, were mysteriously removed from local public records.

The incident would also turn the white Tyson down a long, troubled reconciliation with his Southern roots that eventually led to a professorship in African-American studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Tyson portrays the killing and its aftermath from multiple perspectives, including that of his contemporary, 10-year-old self; his progressive Methodist pastor father, who strove to lead his parishioners to overcome their prejudices; members of the disempowered black community; one of the killers; and his older self, who comes to Oxford with a historian’s eye.

Tyson also got into the backrooms and barrooms where the Molotov cocktails had been manufactured, and into the heads of the young angry blacks who set them off, admittedly responsible for millions of dollars in damage to the town.

He also artfully interweaves the history of race relations in the South, carefully and convincingly rejecting less complex and self-serving versions (“violence and nonviolence were both more ethically complicated and more tightly intertwined-than they appeared in most media accounts and history books”).

Whites retreated behind stately porches; the Klan came in to make a statement about what would happen to anyone who tried to go up against the men who had committed the murder; and the blacks of the town, finally tired of waiting for the rights they had been guaranteed, ran amok.

“ Tyson makes as heroic an effort as anyone could to find redemptive truth through an intelligent cataloging of the complex and distressing facts of the case. In so doing, we are all condemned, and we are all exonerated. In his justification for concentrating so much of his creative life on the examination of the murder of Dickie Marrow, Tyson states, “We are runaway slaves from our own past, and only by turning to face the hounds can we find our freedom beyond them.” — bookreporter.com