And suddenly, it’s ‘1984’ again

Published 12:01 am Sunday, July 9, 2017

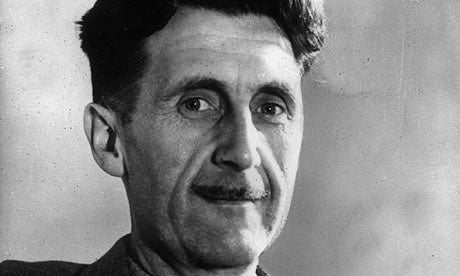

- George Orwell, author of '1984' and 'Animal Farm.'

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

Back in January, George Orwell’s 1949 novel “1984” became a bestseller again.

Penguin publishers have been printing a steady stream of the dystopian novel that gave us words like doublethink, newspeak, thoughtcrime and memory hole.

The book was chosen for the Summer Reading Challenge because of the renewed interest and because Orwell was somewhat prophetic, it seems, in describing a future where alternate facts and fake news are spoken of daily.

Orwell imagined a future where the government controls not just schools, courts and the tax code, Big Brother also seeks to control citizen’s minds.

Protagonist Wilson Smith, in fact, works at a propaganda department for the state, the Ministry of Truth. It’s a place where history is rewritten, where the inconvenient facts are discarded down a memory hole, to be replaced with the new facts dictated by government. So the past isn’t the past anymore. What you remember is a lie, if you remember.

Orwell, in 1949, was worried about totalitarianism, and especially about the way certain governments can alter the past or rewrite documents. In 2017, people are rereading the book in an atmosphere of inflated inauguration numbers, claims of voter fraud and Russian finagling in the elections process.

Newspeak becomes the language of the state, the language used to suppress memories and any rebellious thought.

And we can argue that newspeak began with the internet, where anything can be stated as fact, be rewritten, removed, turned upside down. How many times have you read the phrase “I know for a fact” when there is no such fact, only individual versions of the truth.

For that matter, doublethink, defined in the book as the ability to believe two pieces of contradictory information at one time, certainly applies to internet sources.

This is not the first time the novel has resurged, either. In the 1980s, interest renewed not just because the date was approaching, but because then-president Ronald Reagan was called Big Brother, as opposing political forces saw him as a warmonger.

In 2013, Edward Snowden sparked sales of “1984” with his revelations about U.S. surveillance practices.

In the book, Big Brother is always watching. Everywhere you are, from bathroom to board room, there are screens — everyone is under constant surveillance. And everywhere we are today, we carry those screens with us.

We are glued to smart phones, tablets, computers, televisions, almost constantly. How do we know who’s looking back, or when it will start, if it hasn’t already?

Already, your search of the Internet turns up ads for what you were looking for. Read about a new product? Suddenly it is at the edges of your email, in you browser margins, playing a commercial before your games.

Beyond the ominous words is another story. Love is a crime in the world of “1984.” Failure to acquiesce to Big Brother is treason. Once charged, the thinker is taken to the Ministry of Love, a prison with no windows where torture will force him to relinquish his beliefs and surrender to the authority of Big Brother.

It is at the Ministry of Love where Winston will lose his humanity, where betrayal will finally become easy and his reality will become what Big Brother tells him it is.

Party spies have led him into the trap, and the spies are everywhere — your neighbors, your coworkers, the children in the street. Shades of the Nazi party, perhaps?

Orwell, himself was in a dark place, post-war, desperately ill, writing in a bleak Scottish outpost. He had come up with the idea for the book during the Spanish civil war. During World War II, his flat was destroyed by a buzz bomb.

He and his wife Elaine adopted a son in 1943. In 1945, Elaine died during a routine operation. Orwell neglected his health to work on “Nineteen Eighty-Four” or “The Last Man in Europe.” By the time he sought treatment for tuberculosis, his lungs were seriously damaged.

Orwell died in October 1950, just months after the book’s June 1949 release.

He wrote another novel of political dissent you may have heard of, “Animal Farm” in 1945, based on the events leading up to the Russian Revolution in 1917 and into the Stalinist era.

Though Orwell, whose given name was Eric Blair, died at just 46, his writings remain topical no matter what the era.