UNC historian: Looking back at textiles could provide lessons in years ahead

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, February 8, 2017

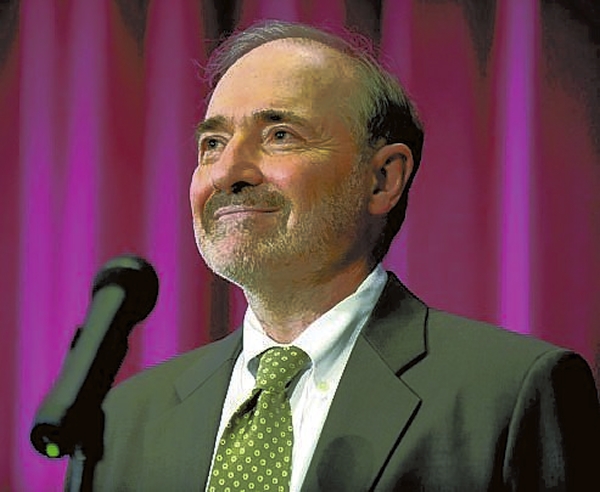

- Historian Peter Coclanis was the guest speaker Feb. 7 for Historic Salisbury Foundation's 'Spinning History: The Rise and Fall of North Carolina's Textiles Industry.' Photo courtesy of Historic Salisbury Foundation

By Mark Wineka

mark.winek@salisburypost.com

SALISBURY — Rowan County, North Carolina and the South as a whole faced the collapse of an agriculture-based economy after the Civil War, and it took entrepreneurs and the communities they lived in to find a substitute.

Most often, that proved to be textile mills.

For 100 years, the textile industry in North Carolina provided decent wages and consistent work for many people who had few other options.

Today, with the loss of many of those same jobs, Rowan County has to find a new economic strategy, much like its leaders did in the 1880s.

Noted economic historian Dr. Peter Coclanis issued that challenge to his audience Tuesday night in Salisbury. A guest of Historic Salisbury Foundation, Coclanis spoke mostly about textile history in North Carolina and Rowan County, but he saved some time for looking at the future.

Talking textiles in Salisbury is like talking about barbecue in Lexington, said Coclanis, the Alfred R. Newsome Distinguished Professor of History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

So he gave two disclaimers: Coclanis said he is not a bonafide specialist in textiles history, though he has written on it and worked with maybe its foremost authority, David Carlton of Vanderbilt University.

Coclanis said he also can’t consider himself a specialist in North Carolina textile history, because more of his work in this area has focused on South Carolina. But he acknowledged borrowing heavily from other N.C. historians, including Dr. Gary Freeze of Catawba College.

Coclanis urged leaders to look at the present-day strengths and weaknesses here and determine where Salisbury and Rowan County might fit economically in the years ahead.

From Coclanis’ outside perspective, the country’s strengths include its location, an excellent transportation infrastructure, reasonably priced housing stock, two large hospitals, several colleges, high-speed internet, a trainable workforce, influential natives living elsewhere who still have a love for Salisbury, strong religious institutions, a prominent arts scene and a documented history of entrepreneurship.

Coclanis said Rowan County, on one hand, has a lot going for it.

But the weaknesses might include an aging population, the lack of growth, a lack of diversity, public schools that need improvements, workers who need new skill sets and the fact that 99 other counties in North Carolina are chasing the same brass rings.

Coclanis said with textiles, furniture and tobacco no longer providing the bulk of N.C. manufacturing jobs, communities such as Rowan County have to look at job sectors such as information technology, chemicals (including pharmaceuticals), food processing, auto parts and banking.

He said leaders should find a way to make Salisbury and Rowan County “sticky” in what is overall a slippery environment of economic development.

Coclanis encouraged those in the audience to look at Rowan’s proximity to Charlotte as an asset and capitalize on it. He told them to think about putting an emphasis on brains, not muscles. He suggested that maybe Rowan County could house back-office operations for IT concerns or further develop its heritage tourism.

The county leaders must work toward transitioning people into new areas of the economy and help give them a middle class existence again — something, it must be said, that the old textile mills once provided.

“It is not to be mourned,” Coclanis said of the 100-year staying power of textiles and the positive influence it held on the N.C. economy.

The peak years for the local textile industries are, of course, long gone.

Coclanis said he looked at Rowan County’s top 25 employers in 2015, and only one company was a textile-related firm.

In 1940, 40 percent of all non-agricultural jobs in North Carolina were in textiles. In 2013, it was only 1 percent.

In the 1970s at its peak, textile employment in Rowan County accounted for more than 5,000 jobs, including roughly 3,000 in Salisbury and 1,000 each in China Grove and Landis, along with several hundred more textile jobs in places such as Spencer, Granite Quarry and Rockwell.

Textile employment fell dramatically from there, even after the Pillowtex plants closed in 2003, creating the biggest single-day layoff in N.C. history. From then until 2009, textile employment in Rowan County dropped from 1,200 people to 296.

Many factors went into the decline of textiles. Technological changes, globalization, currency fluctuations, trade agreements and Chinas’s entry into the market all combined for 30 years of bad news for the South’s textile industry.

In 2015, the average textile wage here was $12.56 an hour. In Bangladesh, it was 19 cents an hour (over a 12-hour day). Ironically, part of North Carolina’s finding a real niche in the textile industry in the early years was its cheap labor.

While the mills did not pay a lot, the money was better than farming.

Millwork provided people with economic stability. The plants led to jobs for many members of the same families, and they built communities that lasted a long time in places such as Landis, China Grove and Kannapolis, which once had the largest unincorporated mill village in the world, thanks to Cannon Mills.

Salisbury’s history with cotton mills starts pretty much in 1839 when the Salisbury Manufacturing Co. (Chambers factory) built on a 15-acre site. Coclanis said this cotton factory lasted about 10 years and later became the site of the infamous Salisbury Confederate Prison during the Civil War.

In 1840, North Carolina had about 25 cotton mills, employing roughly 1,200 statewide. By comparison, Lowell, Mass., had 30 mills, employing 40,000 people.

From 1840 until the Civil War, North Carolina had a reputation of beinga sleepy, backward state, but Coclanis said that reputation was not deserved.

North Carolina was a strongly developing agricultural state, primarily because of cotton, tobacco and a slave workforce.

In 1860, North Carolina had a million people, of which a third were in slavery.

What was a strong agricultural economy before the Civul War, totally collapsed after the war. With the end of slavery, 50 percent of the state’s wealth disappeared without compensation.

In response, some people here tried mining for gold again in Gold Hill. Salisbury tried a tobacco plant for a while. But overall, Rowan County was part of what would become the textile belt from southwest Virginia to northeast Alabama.

Small farms weren’t providing the consistent income families needed, and entrepreneurs started looking for ways to provide jobs. Elsewhere, textiles represented a mature industry in places such as the United Kingdom, parts of Europe and the northeastern United States.

These areas knew how to use centralized production, had developed marketing channels and could make the advanced machinery needed for the mills.

The South became part of a “textile breakout” in the 1880s that had swept into places such as Japan, Mexico, Brazil, Turkey and India, Coclanis said.

From virtually nothing, North Carolina would become the leading textile-producing state in the country by 1924. Southern entrepreneurs lured the technological and marketing knowhow needed by showcasing the cheap labor, abundant water power, inexpensive land and good rail lines.

The South and places such as Rowan County were repositioned as places to do business.

The Salisbury Cotton Mill grew out of an evangelical movement — a crusade to build the factory for economic salvation as much as spiritual salvation. It was operating by 1894, and the Vance Cotton Mill and Kesler Cotton Mill soon followed.

While Rowan County was never the center for the textile industry in the state, it was still a leading textile county (ninth biggest producer) in the leading state in the nation, Coclanis noted.

Bigger companies such as Cannon and Cone would enter the picture in the 20th century, providing the capital needed for growth and gobbling up many of the original plants. Textile mills became wholly integrated in the 1960s and 1970s, leading to more inclusive economic development.

Coclanis described some of the labor troubles, leading to textile strikes in 1929 and 1934 that also spawned increased interest in unions.

Coclanis is married to Salisbury native Deborah Busby. He is a past chairman of the UNC history department and is present director of the Global Research Institute at UNC-Chapel Hill, where he works on world agricultural markets.

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263.