P.D. James short stories remind us how good she was

Published 12:00 am Sunday, December 11, 2016

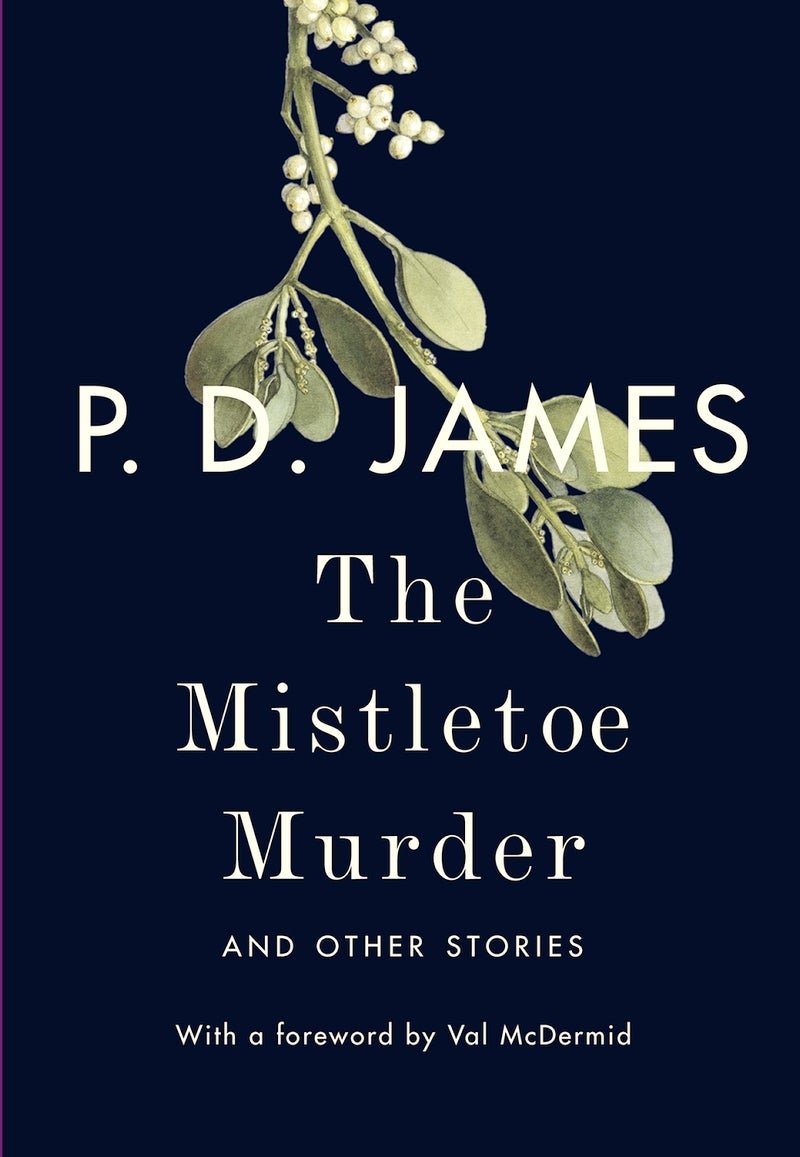

“The Mistletoe Murder: And Other Stories,” by P.D. James. Knopf. 152 pp. $24.

By Dennis Drabelle

Washington Post

Has a great mystery writer ever gone about her craft more self-consciously than P.D. James? She demonstrated her familiarity with the genre not only in her study “Talking About Detective Fiction” (2009) but also in references to predecessors and conventions sprinkled throughout her own fiction.

In “The Mistletoe Murder,” her first and presumably only story collection (James died two years ago, at the age of 94), a nod goes to the woman often called the best-selling mystery writer of all time. “I expect you are thinking that this is typical Agatha Christie,” writes the title story’s narrator, herself “a best-selling crime novelist.” “And you are right; that’s exactly how it struck me at the time. But one forgets … how similar my mother’s England was to Dame Agatha’s Mayhem Parva. And it seems entirely appropriate that the body should have been discovered in the library, that most fatal room in popular British fiction.”

“Parva,” by the way, is Latin for “small.” And Mayhem Parva is not a real town but a dig at the genteel milieu in which Christie’s principal detectives, Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, solved their cases.

The four tales in this slim volume, then, are old-fashioned, at least up to a point: no noir, yet plenty of shadows; no explicit sex, but ample erotic tension. And James spins them with the economy demanded by the short form.

Two of the stories feature that James stalwart Adam Dalgliesh, summed up by a suspect in the novel “Devices and Desires” (1989) as “Scotland Yard’s most intelligent detective.”

“The Twelve Clues of Christmas” is set at a time when the future chief superintendent is a mere sergeant, and it is Dalgliesh himself who places the story in a crime-lit context. As a pedestrian leaps onto a remote road to flag down Dalgliesh’s car one winter afternoon, Dalgliesh’s “first thought was that he had somehow become involved in one of those Christmas short stories written to provide a seasonal frisson for the readers of an upmarket weekly magazine.” As we’ve already been tipped off by the story’s title, that’s not a bad description of the tale we are actually reading.

Many writers of detective fiction deepen their novels by giving their detective a personal flaw to wrestle with as he or she tries to solve crimes. Dalgliesh’s main flaw is atypical— not a weakness (alcohol or drug abuse, say) or an impairment (blindness, amnesia, Asperger’s syndrome, etc.) but a strength. Coming to police work from a higher class than most detectives (his father went to Oxford, and he himself is a well reviewed poet),

Dalgliesh tends to assert his consummate professionalism without making allowances for his colleagues’ feelings. In the aforementioned “Devices and Desires,” a country cop still holds a grudge over a too-frank criticism leveled at him by Dalgliesh during a case they collaborated on 12 years earlier.

My favorite story in this quartet is “The Boxdale Inheritance,” in which Dalgliesh is called upon to perform a task redolent of a Trollope novel. A clergyman who is also a family friend asks for help with a ticklish problem. He is due to inherit a small fortune from a relative who once stood trial on the charge of murdering her rich husband. She owed her acquittal solely to the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard. That is, the evidence pointing to her guilt was robust but not quite conclusive. In such circumstances, the clergyman wonders, can he in good conscience accept the legacy (which he and his family could very much use)? Dalgliesh agrees to delve into the old records and see what he can find out.

Among the many pleasures of reading James is her evocative style. Here she quotes from the Edwardian-era judge’s instructions to the jury as he points out what a guilty verdict would mean to the 20-something accused widow: “She stands before you now, young, vibrant, glowing with health, the years stretching before her with their promise and their hopes. It is in your power to cut off all this as you might top a nettle with one swish of your cane.”

I won’t tell you any more, except to note that the story shows the brilliant Dalgliesh being less nettlesome than usual. And to say what a pleasure it is to have “The Boxdale Inheritance” and its three siblings as postscripts to James’ oeuvre.

Dennis Drabelle is a former mysteries editor of The Washington Post Book World.

(c) 2016, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group