Noah tackles race with honesty, humor

Published 12:00 am Sunday, November 27, 2016

By Connie Ogle

Miami Herald

In his new memoir, “The Daily Show” host Trevor Noah, the child of a Swiss father and Xhosa mother, tells a story that perfectly captures the absurdity of apartheid. Growing up in South Africa when the law prohibited sex between whites and nonwhites, Noah could not be seen in public with his father. When the family went out together, his father walked across the street from Noah and his mother, staying at a safe distance.

One day, his father insisted on accompanying Noah and his mother to Joubert Park in Johannesburg. He tried to walk ahead, but toddler Noah ran after him, shouting “Daddy! Daddy! Daddy!” Terrified, his father fled — the penalty for breaking the law was five years in prison — and Noah chased him happily, thinking they were playing a game. “Where most children are proof of their parents’ love,” he observes wryly, “I was the proof of their criminality.”

The story is horrifying and funny, but blending those two disparate elements of his past is something Noah, 32, has been doing for a long time.

“It’s how I process information,” says Noah from New York, where he’s taking a short break from a frenetic production day for Comedy Central’s “The Daily Show.” “It’s how I work through anything happening in my life. Things are often horrifying. If I don’t laugh, I’m never going to laugh. I find the funny in everything and go from there. I think when it came to the book, putting those pieces together, the stories formed themselves. Life isn’t one-dimensional. It’s horrifying and funny at the same time.”

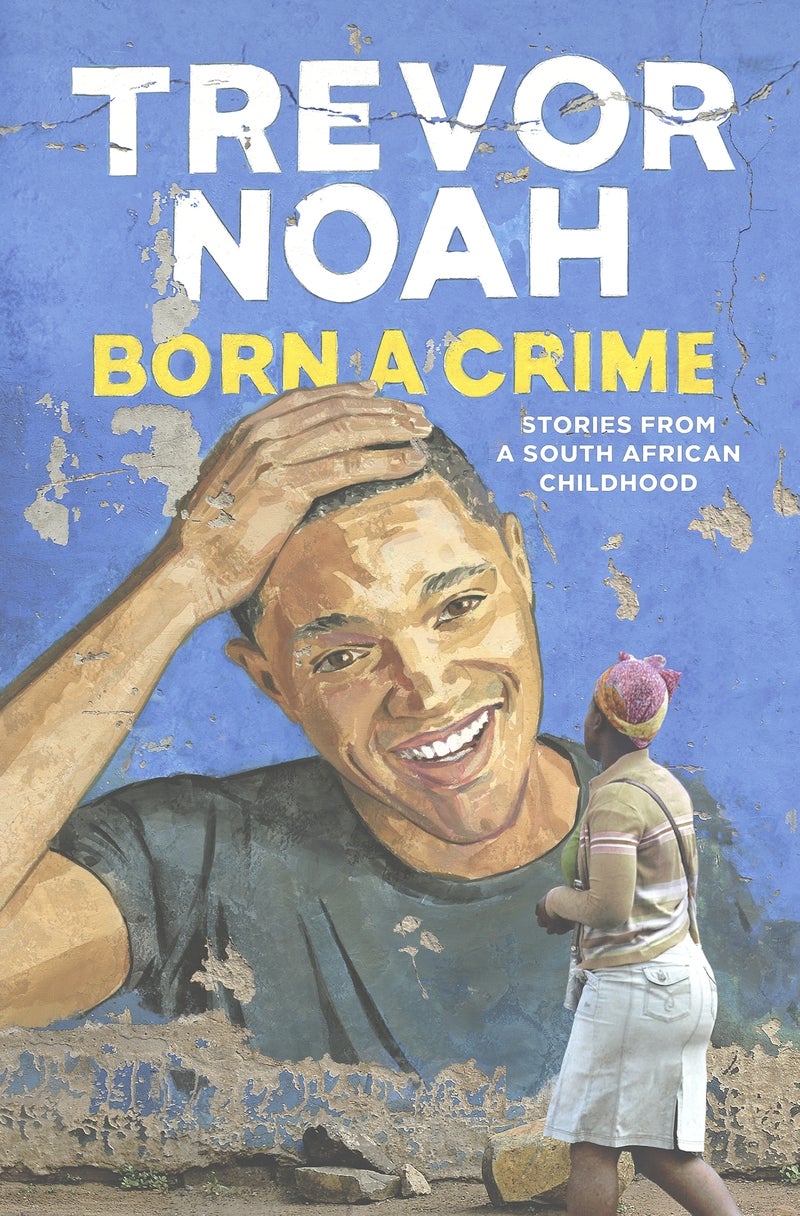

In “Born A Crime,” the comedian recounts his childhood, adolescence and young adulthood in South Africa during apartheid and its chaotic, repressive aftermath. Despite the fact that the memoir tackles such subjects as racial injustice, poverty and an abusive stepfather who eventually shot (but didn’t kill) Noah’s mother, “Born a Crime” can be amusing. (On the fact his mother and grandmother were always afraid his grandfather’s second family would poison them: “It was like “Game of Thrones” with poor people”). But Noah’s unique perspective of a racially divided world sounds hauntingly relevant in light of our own political and cultural divisions.

“Born a Crime” doesn’t really cover Noah’s professional life, his years working in South African radio and TV and his eventual move to stand-up comedy, which led him to the “Daily Show” gig (a prime job that comes with more than its share of criticism). He took over hosting duties from Jon Stewart in September 2015.

Replacing the beloved Stewart was surely tougher than writing a book, but Noah says “Born a Crime” forced him to really examine his history.

“The biggest obstacle I had to get over was discovering the truth about things, about my feelings, the world I lived in, the truth about my experience,” he says. “In real life, we don’t have to deal with that. We try to move on from the hard things as quickly as possible so we’re in a better place.

“The personal stuff was hard to write because it puts you in a vulnerable position. How much of myself am I willing to share? But there’s no point in me writing a book if I’m not going to give everything. … I came to realize you’re just going to have to lay it out there. If you want to write the book, write the book.”

So he writes about how he was a naughty child who took advantage of his skin tone (his grandmother had no problem hitting his cousins but wouldn’t punish him because “I don’t know how to hit a white child. Trevor, when you hit him he turns blue and green and yellow and red.” When times were lean, he sucked the marrow out of “soup bones” usually destined for the dogs (“a skill poor people learn early”).

Growing up in a world where racial labels — black, white or colored — defined every aspect of life, Noah has a singular viewpoint about America’s own struggles with race.

“I think if you lived through it, being from South Africa, it prepares you for this conversation,” he says. “We’ve had them and continue to have them in an open manner, a more blunt manner than in America. American conversations don’t seem to be happening in a progressive way. The conversation isn’t people addressing the issues but asking first whether or not there is an issue, which is a different conversation than I’m used to. In South Africa, we all acknowledge there was an issue, and here people are going, ‘Is there an issue?’ ”

That disconnect, he says, is not something he’s only witnessed in America.

“I became more aware of this the more I traveled,” he says. “I see how many things people perceive as the biggest problem in their world, and yet some other realm sees it as something not important. Think of gender equality. From many men’s perspectives there is no issue, but women say it’s the biggest issue facing them. It’s the same thing with race. Black people complain about the issues and white people are going, ‘That’s not the only thing happening in the world.’ But if you’re black, that’s all that’s happening.”

“We’re in a place where more and more, if we’re not careful, we are going to exist completely in bubbles that are devoid of information that is unbiased and neutral,” he says. “People base everything they do on sides, on what side they’re on. One of the greatest gifts and curses of our generation is the internet and social media. This morning I was looking at a fake CNN site and thinking, ‘I wonder how many people click on this thinking it’s real?’ There’s no way to stop that. It’s a scary thing.”