‘The Risen’ — no joy in a return to the past

Published 12:00 am Sunday, October 30, 2016

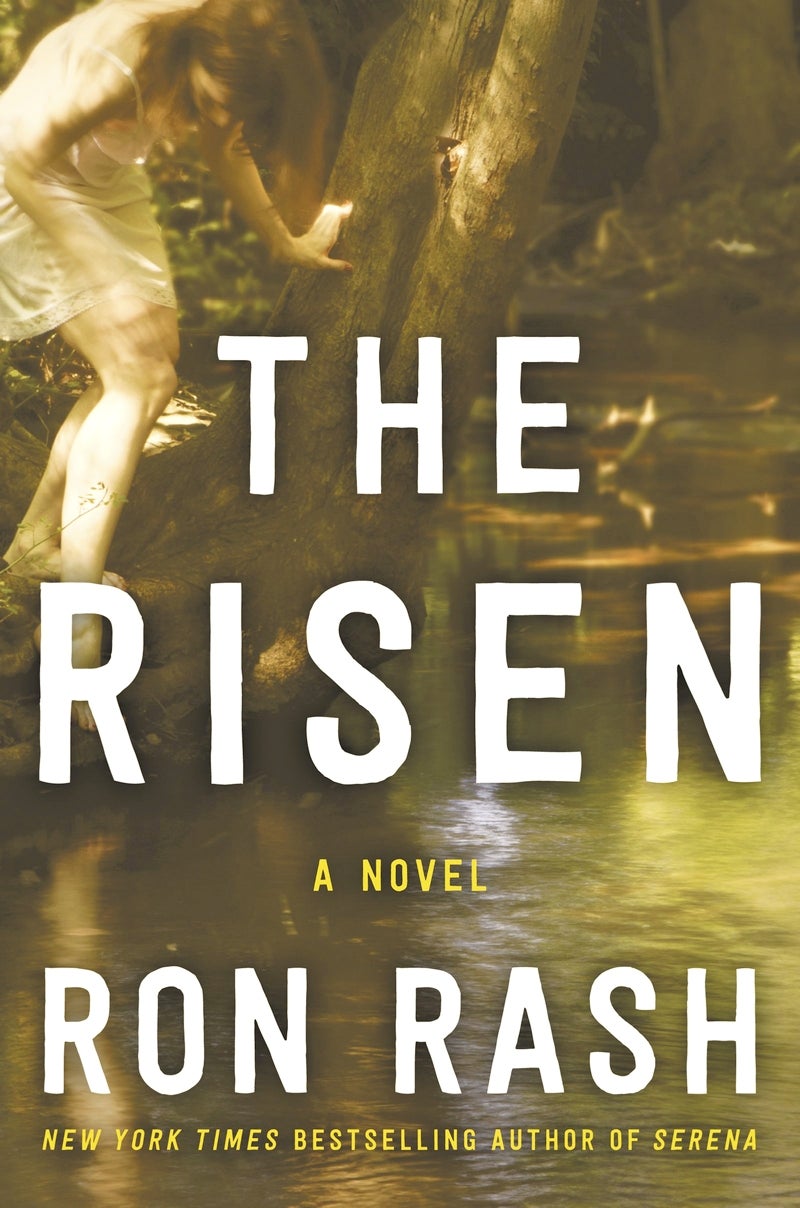

- In 'The Risen,' Ron Rash shows the consequences of bad choices.

‘The Risen,” by Ron Rash. Ecco. 2016. 272 pp. $27.99.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

For Ron Rash, North Carolina’s mountains hold menace. In the hills and valleys, danger lurks, in the natural world, in the humans who inhabit those isolated places, in the shadows and the mist.

There is no solace in a cool mountain stream, no joy in a favorite fishing hole.

All is tinged with blood — revenge, anger, desperation.

So it is in “The Risen,” where Rash spins another cautionary tale of love and death, devotion and betrayal.

Often in Rash’w work, families are divided, split apart by the actions of one member, or by outside forces too powerful too control.

When the drug culture eases into the small towns and deep woods in the late 1960s, pleasure leads almost exclusively to pain.

Sins are magnified and swift payment must be made. Is there justice? Only in a twisted form, a vigilante justice that defines itelf by needs, not by rules; by instinct and not evidence.

Brothers Bill and Eugene are the hapless perpetrators and victims when an exotic teen-ager emerges from a pool near their Sunday fishing spot.

Clad in a bright green bikini and having, seemingly, no boundaries, Ligeia, as Eugene calls her, rises like a nymph from the water, and begins working her magic — her radical thoughts and actions — on the boys. Bill is in college, Eugene still in high school. Their lives are ruled by the iron will of their demanding grandfather, who praises them with threats of denials, distress and disownment.

Their doctor grandfather is an exacting and punishing man who forgets no slights, forgives no errors and holds not just his grandsons and their mother in thrall, but much of the small town.

And he’s going to find out about the boys’ well-kept secret of the unusual girl from Florida.

Ligeia shows up with a plausible, if overworked story. Her parents in Florida, parents who appear to be less than competent themselves, have sent her away, to get her out of the trouble she’s in in the Sunshine state. Pawned off on her unsuspecting aunt and uncle and living in isolation, she is only allowed to attend high school and church. She cannot go out or have friends over. So she sneaks away to swim in the stream — her way, she says, of getting out from under the oppression of her straight-laced relatives.

But like every good delinquent, she knows how to make connections. Whether she knows Bill and Eugene have access to drugs from the start, or is just lucky enough to find the right saps is never clear.

It’s easy for her to offer sex for rewards. First Bill enjoys her and brings her alcohol. When she asks for a little Valium, he takes one pack from his grandfather’s medicine closet at his practice.

Bill’s smart enough to know he can’t keep doing that. But when Ligeia turns her interest, her favors and her requests to Eugene, he just wants to please her and does what she asks.

In the process, Eugene tastes his first beer, and it’s obvious almost at once that alcohol will be his lifelong passion, crutch and demon.

The story is told looking back at the summer of Ligeia after Eugene reads in the paper that her body has been found near Panther Creek, their old fishing hole. After downing a pint of jack Daniels, Eugene calls his brother, the successful surgeon Bill, desparate to know what happened.

Rash has the brothers at odds, with Bill a shining light of success, married to his college sweetheart, successfully saving lives as the surgeon his grandfather always wanted. Eugene is an alcoholic who nearly killed his own daughter in an accident. Now he bathes in self-loathing, alone with hsi only friends — the bottles of alcohol that dull the pain. Eugene teaches at a community college, having lost a better job and the will to write — which had been his gift.

But is all as it seems? Eugene begins to have debilitating fears about his brother and what might have happened.

The book relives those days in 1969, the encounters with Ligeia, the evidence of the cruelty of their grandfather and the helplessness of their mother.

As teens, Bill and Eugene work in their grandfather’s office most days of the summer, running errands, answering the phone. Grandfather even lets Bill do some suturing now and then, to practice. On Saturdays, they wax and buff the floors and Nebo, their grandfather’s mute handyman, mows the lawn and checks on what they’re doing.

So they have access to the closet full of medication samples, but Bill, tells Eugene, “We’re not going to be stupid, little brother.”

The tale is a loud message to be careful about your choices. One bad choice and your life could be ruined forever. But the morality is slippery here — one man’s choice can also be deadly as he plays a false god wreaking vengeance.

The scene is set, the story compelling. The characters can be startling. Their interactions are strained, as if seen through a fog. Perhaps that’s the past.

See more book news and reviews