Doyle McManus: What another Romney run means

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, January 20, 2015

Technically, the number of formal contenders for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination is still zero. But a huge and impressive field of almost-candidates has already turned the contest into a crowded, noisy brawl.

The starting gun was Jeb Bush’s announcement last month that he was “exploring” a race and raising millions of dollars in case his exploration got somewhere.

That startled the rest of the field the way gunshot startles birds, and many of them fluttered into panicky action.

Most of the names aren’t a surprise. Chris Christie, Ted Cruz, Rand Paul, Mike Huckabee, Scott Walker and others have mused more or less openly about running for president for months.

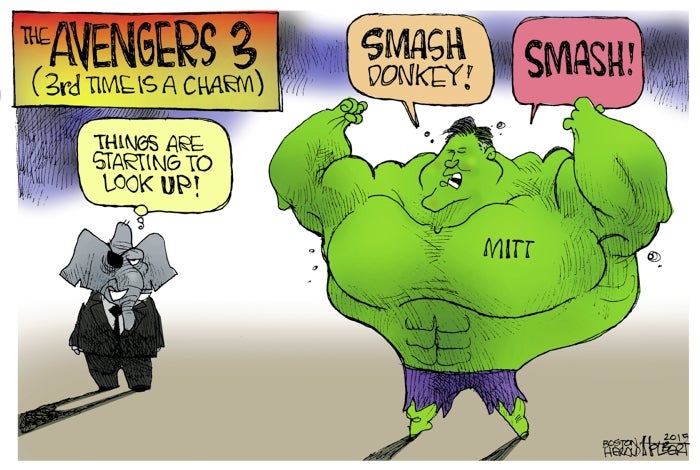

But one sudden entrant startled even some of his own former advisors: Mitt Romney, the GOP’s nominee in 2012, whose last campaign is remembered by many Republicans as a noble but ill-managed failure.

“I want to be president,” Romney told a roomful of fundraisers in New York. He summoned old lieutenants away from dalliances with other candidates. He called former donors to ask them to wait before committing to anyone else. He flew to San Diego to give a speech to the Republican National Committee.

But if Romney’s declarations were an attempt to test the waters, a lot of the water turned brackish fast.

“The definition of insanity is to do the same thing over and over again and expect a different result,” Rand Paul told the New Hampshire Journal. So much for the old commandment against speaking ill of a fellow Republican — but Paul is a likely future competitor. What about Romney’s old supporters?

“I don’t know, man,” said an uncharacteristically tongue-tied Sen. John McCain, who backed Romney in 2012. “It’s a free country. … I thought there was no education in the second kick of a mule.”

“There’s not a lot of good precedent for somebody losing the election and coming back four years later,” former Rep. Vin Weber (R-Minn.), a co-chair of Romney’s 2012 campaign, told Bloomberg Politics. “I think Gov. Romney had two increasingly good years after losing the presidency, and now he’s had one pretty bad week.”

So Romney faces an uphill battle to persuade his party that he could be a better presidential candidate this time than he was four years ago, not to mention convincing voters that his central message — that as a successful businessman, he could revive a moribund economy — makes more sense now that the economy is doing better.

In the face of all this, Romney’s evident desire to run again tells us two things.

First, five years after the 2010 tea party insurgency, the Republican establishment isn’t dead; instead, it may be stronger than ever.

Most of the 2016 GOP action was expected to come from hyperactive conservative factions: the insurgent senators (Cruz and Paul), the fiscal-hawk governors (Walker, John Kasich and Mike Pence) and the social conservatives (Rick Santorum, Ben Carson and Huckabee).

Instead, Bush, Romney and Christie — the establishment — have sparked the first fireworks. The mainstream is still where most Republican primary voters are, as Romney showed in 2012. It’s where most of the big donors are. And it’s still the party’s most likely source for a general election win in 2016.

“The tea party was primarily a reaction to Barack Obama,” Weber argued. “It hasn’t gone away, but it’s not going to dominate the future.”

Second, Romney’s eagerness to jump into the ordeal of a national campaign is a reminder that people run for president for many reasons.

Some, like Jeb Bush or Hillary Rodham Clinton, run not only because they think they would be good presidents, but also because it’s a role for which they’ve been training all their lives.

For the flock of younger contenders, the question instead is: Why not? Politicians’ careers rarely suffer if they run for the nomination and lose; quite the contrary. They gain experience and a bigger list of donors. And if they do better than expected, they land on the list of serious contenders for the next cycle.

Others run to mostly promote ideas (former Rep. Ron Paul). And for others, there’s at least the suspicion that they’re running to boost their careers as commentators and book writers (Huckabee).

In Romney’s case, though, there’s an additional impetus: a successful man’s hunger to erase the stigma of failure.

“I have looked at what happens to anybody in this country who loses as the nominee of their party,” Romney said at the end of the 2012 campaign, in a moment captured by the documentary “Mitt.” “They become a loser for life. … We just brutalize whoever loses.”

A presidential campaign is an inescapably messy process. The Republican National Committee, at its meeting in San Diego last week, said it hoped to bring more order to its portion of the contest this time. The drama of the last few weeks suggests that may be easier said than done.

McManus is a columnist for the Los Angeles Times.