Once enemies, now friends: Annual Iwo Jima reunions

Published 9:39 am Monday, October 27, 2014

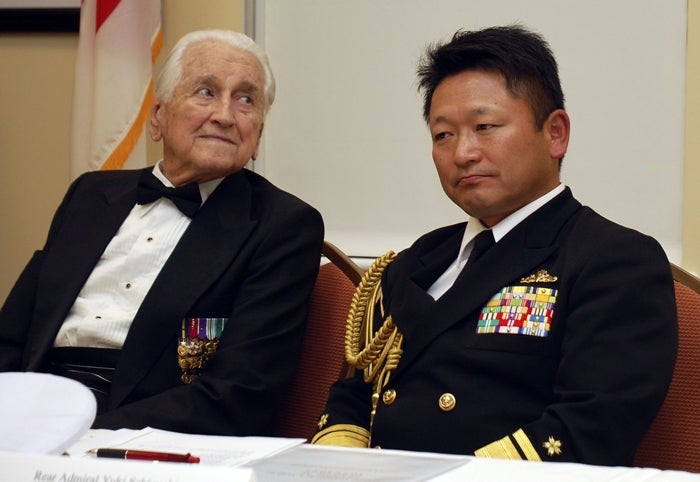

- Mark Wineka/Salisbury Post Battle of Iwo Jima veteran Lt. General Lawrence F. Snowden (U.S. Marines-Ret.), left, and Rear Admiral Yuki Sekiguchi, defense attache at the Embassy of Japan in Washington, D.C., listen to another speaker during a program about United States-Japanese relations held Sunday afternoon at the N.C. Research Campus in Kannapolis.

KANNAPOLIS — Lt. Gen. Lawrence F. Snowden, a retired Marine who fought 36 bloody days at Iwo Jima during World War II, said he required a personal transformation to let go of his hatred for the Japanese.

He shed those feelings long ago, and it has been Snowden, founder of the Joint Reunion of Honor for both Japanese and American veterans of Iwo Jima, who has led emotional trips back to the island for 19 straight years.

“Who’s more surprised than I am?” Snowden asked Sunday afternoon at the N.C. Research Campus. “Nobody.”

After the last Iwo Jima trip, the 93-year-old Snowden was hospitalized five days for exhaustion. But plans already are in motion for the 20th Joint Reunion of Honor in March 2015, and Snowden promises he will be there.

Snowden was one of several speakers Sunday for a program titled “The Real Japan,” sponsored by Japan Carolinas. Other speakers during the two-hour program included Dr. Julia Nesheiwat, deputy assistant secretary for energy for the U.S. State Department, and Rear Admiral Yuki Sekiguchi, defense attache at the Embassy of Japan in Washington, D.C.

Nesheiwat spoke on “womenomics” and the role women will play in the Japanese economy and workplace in coming years.

Sekiguchi covered the U.S.-Japanese partnership after the March 11, 2011, earthquake, tsunami and nuclear reactor disaster and the continuing security alliance Japan has with the United States.

But it was Snowden for whom the audience saved most of its questions. A resident of Tallahassee, Fla., Snowden is thought to be the most senior U.S. military survivor of Iwo Jima. He threw in a bit of caution, however.

Neither side — Japanese or American — knows how many survivors are left.

γγγ

The Japanese have since renamed Iwo Jima to “Iwo To,” and it is not the easiest place to visit, especially for the Americans who attend. Coming from various points, the group eventually stages in Guam before taking a charter flight to the former Iwo Jima, which has few amenities.

Those who visit for the reunion are only allowed to do so for one day — between sunup and sundown. They must pack their own water and box lunches and arrange for their own medical personnel.

Over the years, Snowden has made it his personal mission to make sure the American contingent recognizes the day on the island is not a victory tour. Rather, the visit and ceremonies connected with it are simply meant to honor the dead from both sides.

If you can’t do that, Snowden tells his veterans and their families, don’t go, or he’ll prohibit you from making the trip.

Snowden said one of his Iwo Jima veterans, a dentist, showed up at an airport with a necklace made out of the gold teeth he had taken from dead Japanese soldiers on the battlefield. The dentist did not make the trip with that necklace.

In trying to make preparations for the first reunion in 1995, Snowden recalled, Japanese bureaucrats were worried the American veterans would use the trip to crow about their victory.

γγγ

The numbers of veterans who are survivors of the battle and actually make the trip are usually small. For the Japanese, Snowden said, being a survivor of Iwo Jima is an especially complex situation.

Four years ago, five Japanese Iwo Jima survivors attended the reunion; this past year, none. “We never know until we get there,” he said.

The Japanese survivors were viewed in two ways back home, Snowden said. As defenders of the island at the time, rather than be captured, they were expected to kill 10 Marines before taking their own lives, Snowden said.

Capture meant failure, and it was a stigma the men carried with them back in Japan.

But another part of Japanese society recognized in defending the island, the survivors did all they could do. There were roughly 23,000 Japanese deaths at Iwo Jima, and less than 1,000 who ended up as prisoners.

For the day of the annual reunion, Japanese men and women wear traditional mourning clothes. As part of a ceremony, Japanese participants take a bucket of water consecrated by a Buddhist priest in Tokyo, and they walk around a monument to the Japanese dead spreading the water.

In the six months before U.S. forces arrived to try and take Iwo Jima, the Japanese soldiers were on half rations of food and water because a U.S. blockade had prevented supplies from getting to them.

γγγ

Survivors who do make the reunion usually are given priority in getting transportation to the top of Mount Suribachi. Snowden said a lot of the other visitors prefer to walk up to the top, where the views are magnificent and the five-mile-wide island can be seen in all directions.

An empty flagpole stands next to the Marine Corps monument on top of the mountain, and the U.S. visitors are encouraged to bring flags which they can take turns in running up the pole.

A Marine Corps band also gives a concert, and many dignitaries from both countries make speeches. The Japanese contingent at the last reunion included five vice ministers and 17 members of Japan’s congress. Snowden expects U.S. Ambassador to Japan Caroline Kennedy to be at the 20th reunion in March.

The first reunion in 1995 was supposed to be a one-time deal, but Snowden felt compelled to keep it going after hearing the words of the keynote speaker, the widow of Tadamichi Kuribayashi, who had been commander of the Japanese garrison at Iwo Jima, where he died.

Speaking in classical Japanese, the widow basically said, “Yesterday we were enemies, today we are friends, and we must never let this kind of warfare happen again.”

γγγ

The reunion has become an “alliance-building event” that Snowden believes grows in importance every year.

He said he often has been asked by fellow World War II veterans how he could be involved with an enemy whom he fought hand to hand and eyeball to eyeball and with the belief it was kill or be killed.

At Iwo Jima, Snowden was wounded twice, and he said he already had bought fully into the U.S. wartime propaganda and sentiment against the Japanese people, especially as he was hopping island to island fighting the enemy.

“It took a major change in attitude,” Snowden said of his feelings after the war.

The attitude change during the Korean War in 1953 when a major ordered Snowden to travel to Japan for three days and nights of logistical meetings.

At the time, a number of Japanese companies were engaged in shipping supplies that supported U.S troops in Korea, and during his stay in Tokyo, Snowden ate meals and drank beer with many Japanese hosts.

“They were just like I was,” Snowden said.

During the war, they had been concerned about their families, and the Japanese who fought at Iwo Jima didn’t want to be there any more than he did.

“Once we were there,” Snowden said, “we did what we had to do. Those were enemies, but now they were friends, helping us win in Korea.”

He said he thought to himself how silly his hatred for the Japanese people was.

Years went by and Snowden eventually was sent to Japan as chief of staff of U.S. forces there, and he said he went with his better frame of mind intact. He also served later as president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Japan.

Snowden said the reunions have become particularly important to the families of men from both sides who were killed and whose remains are still on the island.

He expects the March 2015 Iwo Jima reunion — in the 70th anniversary year of the battle — to include about 280 people.

“It’s going to be a big event,” Snowden said.

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263.