Satire marks insider’s look at N.C. politics

Published 12:00 am Sunday, July 6, 2014

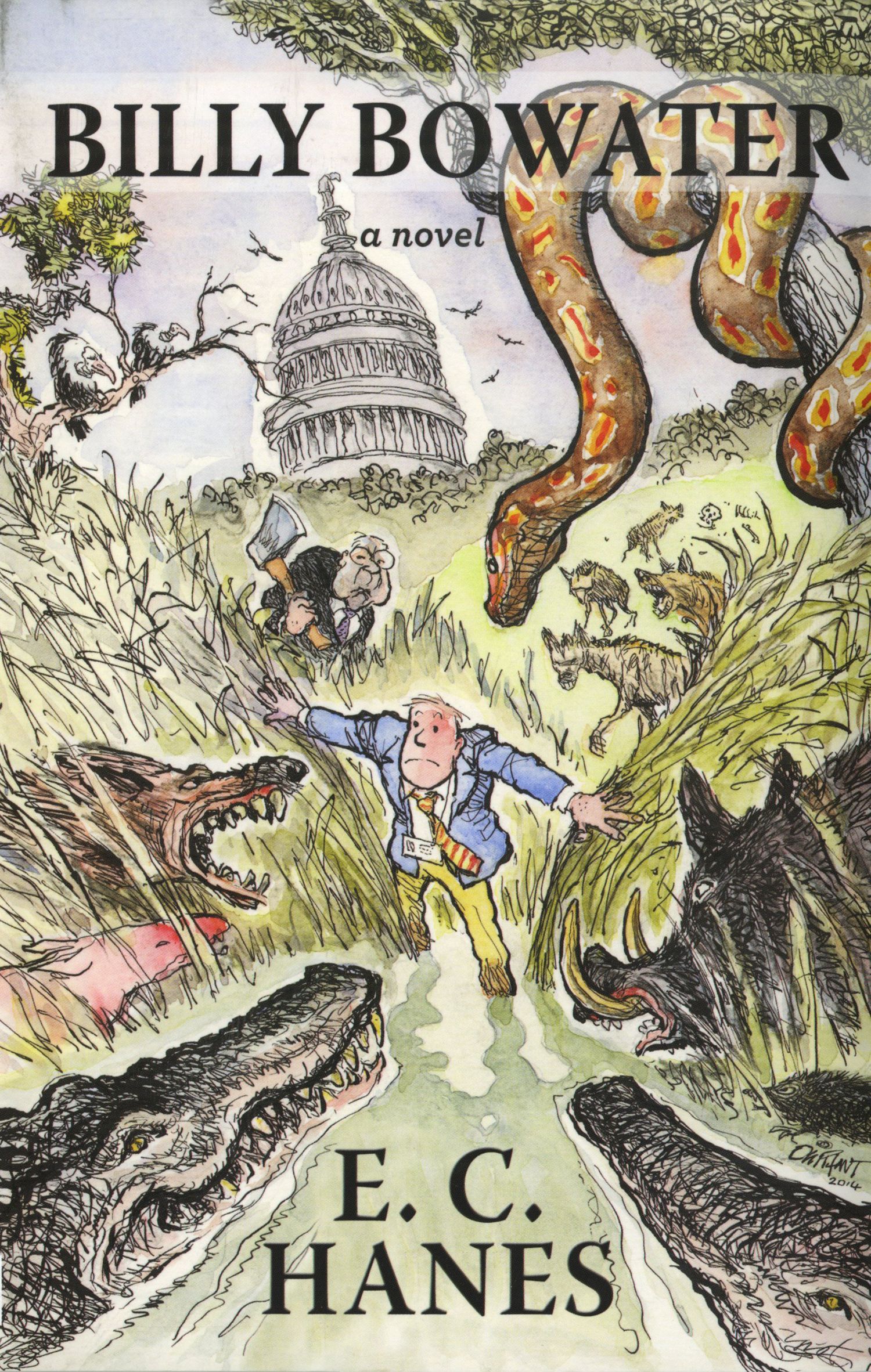

“Billy Bowater,” by E.C. Hanes. Rane Coat Press. 2014. 200 pp. $24.95.

In addition to death and taxes, there’s one thing you can be pretty sure of: Campaigns are full of lies and liars — on all sides.

The problem arises when one of those called on to adopt a convenient lie begins soul searching. “Billy Bowater” is a first- person account — fictional, but only just — of the soul of one William Walpole Bowater III, sold for power. It is author E.C. Hanes sort-of biography. The names have been changed, but there’s no doubt who and what he’s talking about.

Billy Bowater ditches the family law firm in Warren, N.C., the one started by his father, the former attorney general of North Carolina, after a misunderstanding with the bar. He heads to the more exciting world of Washington, D.C., where he has a job as the administrative assistant for Sen. Wiley Grace Hoots. Yes, think Jesse Helms (and look at the cover). It’s time for another election, and Wiley, who happens to be a good-ol’ ultra-conservative, needs fuel for his fire. Billy, tugging his forelock and swearing allegiance to the boss, does what he is asked to do.

It’s his near constant self-defense that lets readers know he really isn’t the heartless flak he acts like. No, no. He’s just doing a job. He explains it to his former college roommate: “… I do a job and that’s to keep the senator informed, on time, and focused. If he wants my opinion he’ll ask for it, and as of now he hasn’t and I haven’t expressed it. Truthfully Wiley doesn’t want anybody’s opinion, but what he does want is for things to go his way. I try to make that happen. Washington, as you well know, is about power, its acquisition and its maintenance, so I try to make sure that he has the power he wants and needs. I’m his enabler as well as his influence accountant. …” His old friend isn’t impressed either, walking away with a worse opinion of him.

This claptrap doesn’t sit well with his lover, a Raleigh News & Observer reporter named Lucy Sue Tribble (there’s another North Carolina name), who continually challenges him and expects him to be true to himself, not to the ideology he spouts like cornflakes on a bad morning.

Lucy Sue, whose salty language and cynical attitude are a little cliched, acts as Billy’s conscience. But the guy with horns on the other shoulder seems to be winning.

Hoots, Tribble and later, Art Bishop — the names speak loudly. Everyone must know who they are in this book, and all the followers and detractors know exactly who Hanes is talking about, too.

In this morass of compromised beliefs and morals comes the subplot: Hoots’ daughter is offended by an art show at the Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill, an NEA-sponsored show of Generation X art. The show includes a painting of one man urinating on another and a photo of two young girls embracing under a waterfall.

If this begins to remind you of something, go no further than author Hanes’ bio on the front and back flaps of the cover and you’ll find his reference point. Do the names Serrano and Mapplethorpe ring any bells? In real life, the exhibition was at SECCA, Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art, in Hanes’ own town of Winston-Salem.

Hanes lays it on pretty thick with the artists’ names, too — Christian Pope and Aeriel Sopwith.

Hoots’ mantra becomes deviant and pervert. But Billy, wily Billy, guides those ugly words through a powerful television evangelist, who promotes Hoots as a man who’ll defend American virtues.

Lucy Sue is disgusted by the whole thing, and wants to tell the whole story, wants to make the artists real people. One ignores her, and the other, exposed, damaged and desperate, confides in her. Lucy is determined to help the young woman and lays down the law with Billy. All she gets is more excuses.

But something is chipping away at Billy’s psyche. He asks Hoots to drop the artists’ names from his popular diatribe. That’s when the good senator levels a beady eye on his boy wonder and gives him ultimatums. Cue the tragedy. Even that doesn’t burn Billy quite enough.

It’s not that so much happens here, it’s that so much is revealed during one man’s search for who he really is, and his constant protestations that no one can know him because no one has experienced what he has are a load of manure. The artist Christian Pope spouts the same rhetoric, much to Billy’s relief. “I think Christian is also right about the impossibility of knowing another’s soul. We can pretend; we can wish, we can even lie, but we’ll never see inside. Never!”

Billy’s got plenty of excuses for who he is and what he does; he loves power and deference and all the trappings of Washington. But he’s never going to let anyone know what he believes. Just like many politicians.

The truth really is stranger than fiction.