‘Ghosts ships of Normandy’

Published 12:00 am Thursday, May 29, 2014

SALISBURY — In 1955, Wade L. Edwards was working for Western Electric in Winston-Salem when a co-worker said he was wanted at the front desk.

As Edwards walked into the lobby, five Army soldiers — military police officers — surrounded him.

“What’s the problem?” Edwards asked.

“You’re under arrest — desertion in the time of war,” a major with the group said.

Edwards was confused. He had served with distinction in the U.S. Navy and was on board one of the “ghost ships of Normandy” during the D-Day invasion in World War II. A decade earlier, after three years of service, the Navy gave him his honorable discharge Nov. 13, 1945.

Edwards hastily explained all of this to the major, who remained skeptical.

“Can you prove it?” he demanded.

Edwards asked that he be driven to his home in Ardmore, and while he remained handcuffed, he directed them to a drawer holding his service documents.

“I’ll be damned,” the major said. After Edwards made some concerted pleas for the men’s help in straightening out this misunderstanding, the major agreed to let him go but promised Edwards he would be hearing soon from the Army.

Officials apparently thought Edwards had been inducted into the Army, not the Navy, in 1942 and had been AWOL ever since.

Today, Edwards loves to tell people how he was serving in both the Army and Navy during the war. A few weeks later, he received a letter from the Army, saying he was cleared of any responsibility or wrongdoing.

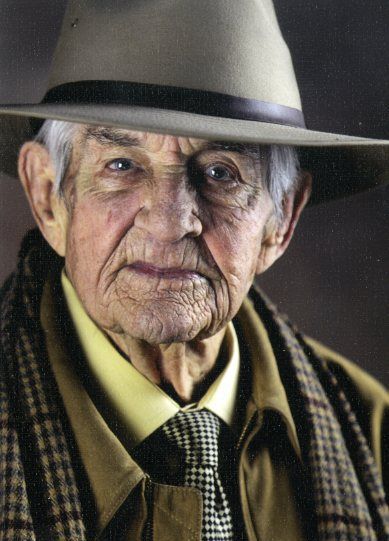

Edwards, 92, will be among the many veterans on hand to share their wartime experiences Saturday at the annual D-Day Remembrance held at the Price of Freedom Museum in China Grove (see box).

Edwards describes himself as a “belligerent young man,” who ran away from his N.C. home when he was 14 and ended up in Jamestown, Va., eventually graduating from a high school in Williamsburg.

He worked as a telephone installer in Washington, D.C., where an aunt lived, and also served in the U.S. Army National Guard, from 1939-41.

With the country on the brink of war, Edwards desperately wanted to join his brother, Charles, in the Navy, and he let his feelings be known to his Army National Guard corporal, sergeant, lieutenant and lieutenant colonel, while serving with Co. K of the 1st Virginia Infantry.

But on the November night Edwards and his fellow company members were supposed to be inducted into the Army, he walked off the base, rode a bus to Raleigh and joined the Navy on Nov. 21, 1942.

Edwards says he lied to the Navy recruiter when he said he had never been in the service. He didn’t know it until 1955, but Edwards had been inducted into the Army that night he walked off the base in Virginia.

In the Navy, Edwards went to various schools, trained as a radioman and signalman and was assigned as part of the Naval Armed Guard on Merchant Marine ships which supplied the military with goods and equipment.

The Navy installed powerful anti-aircraft guns on the Merchant Marine boats and also provided them with communications personnel such as Edwards, who found himself on eight different merchant vessels carrying cargo to England, Ireland, Russia, Italy, North Africa and Sicily.

In the days before D-Day, June 6, 1944, Edwards was assigned to the merchant ship SS Olambala, which sailed under the Panamanian flag. Docked at Liverpool, England, the rusty ship left port about 1 a.m., and as Edwards slept, chugged its way across the English Channel.

Edwards says he woke in the morning to the sight of what seemed to be 10,000 ships off the coast of France.

He didn’t know it then, but the Olambala was going to be part of what became known in history as the ghost ships of Normandy. Fearful that foul weather could make a beach landing of troops impossible, the Allies decided to scuttle dozens on dozens of old, battle-worn, torpedoed, mined and really derelict ships, hoping the purposely disabled boats would create a breakwater about 1,000 yards off the D-Day beachheads.

The block-ships, such as the Olambala, were called “corn cobs.” The Normandy invasion was their last hurrah, and some of the less seaworthy ships even had to be towed into place.

One account after the war puts the number of scuttled ships at 89, and they were sunk into shallow water that Edwards estimated to be about 16 feet deep. He said he was part of a line of 38 ships — one of the “gooseberries” set up to create what the British called a “mulberry harbor.”

The mulberry helped in the off-loading of troops and cargo onto the beaches of the Normandy invasion. Explosive charges were strategically placed in the hulls of the ships to cause their half-sinking.

The Naval Armed Guards remained on the sunken merchant ships, and were involved in fire fights with the Germans as the gooseberries were being formed and the invasion readied.

Edwards and the rest of the Naval crew on the Olambala stayed in the mulberry harbor until June 25, when Edwards says he was put on a speed boat to cross the English Channel. From there, he traveled by train to Glasgow, Scotland, then sailed on the Queen Elizabeth home for a 30-day leave in DeLand, Fla.

He finished out the war on the S.S. Fitzhugh Lee, taking a seven-month roundtrip with stops in Africa and Italy to supply Allied forces with war materials.

Edwards’ Navy brother, Charles, was killed toward the end of the war when the destroyer he was on, the Drexel, was hit by a Japanese suicide bomber, which struck the ship’s powder magazine. Charles Edwards was only 26.

Wade Edwards attended Wake Forest College after the war and enrolled in medical school until his funds from the G.I. Bill ran out. Living in the Winston-Salem area since 1947, he went on to have a 30-year career with Western Electric and AT&T before retiring in 1981.

Edwards kept busy. He became a salesman for Modern Chevrolet in Winston-Salem and Parks Chevrolet in Kernersville, then he sold real estate for five years.

“Don’t lie to anybody,” Edwards says was his secret in the car business. “Get them to trust you, and they’ll do business with you.”

Over the years, Edwards and his wife, who died about four years ago, adopted a son and daughter. Today, he routinely drives to Salisbury to visit a lady friend at the Carillon assisted living facility and to sometimes stop in and see Bobby Mault, one of the founders of the Price of Freedom Museum.

“I think he’s one of the most deserving Americans I’ve ever run into,” Edwards says.

Edwards earned several medals for his service during the great war — just don’t tell the Army.

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263, or mwineka@salisburypost.com.