Art and the Red Sox: Baseball great Billy Goodman part of Rockwell masterpiece

Published 12:00 am Sunday, May 11, 2014

SALISBURY — The late Billy Goodman was a heck of a baseball player. His daughter, Kathy Goodman Simpkins of Cornelius, will tell you he was an even greater father.

Goodman used to wake his daughter up for a breakfast he always made, pick her up at school, take her fishing or hunting and allow her to pal around with his close baseball friends, such as Boston Red Sox greats Johnny Pesky and Ted Williams.

Goodman even named his boat in Florida the “Kathy Jane,” for his little girl.

“He was totally my idol, the coolest man I’ve ever known,” says Simpkins, who works in downtown Charlotte for Adecco.

Billy Goodman died of multiple myeloma in October 1984 when he was only 58. Now 30 years later, his name has crept back into the consciousness of baseball fans and, yes, the art world with the pending sale of a famous Norman Rockwell piece.

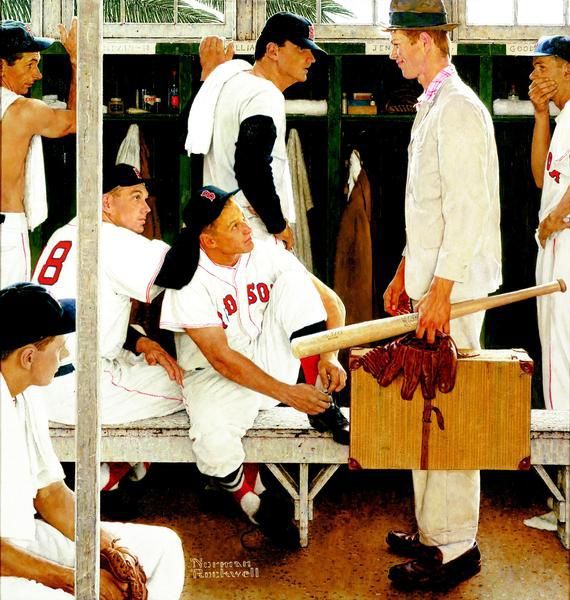

That painting — “The Rookie (Red Sox Locker Room)” — may be worth upwards of $30 million, and Goodman is in it. He and a handful of other Boston Red Sox players posed for Rockwell at the painter’s Stockbridge, Mass., home.

The 1957 work depicts a fresh-faced prospect — bat, glove and beat-up suitcase in hand — arriving to spring training. In a suit that’s way too small for him, the rookie ballplayer is meeting the gazes of wily veterans sizing the hayseed up.

Goodman stands at the far right, with a hand over his mouth, possibly trying to stifle a laugh.

Other players in the Rockwell painting, which served as the March 2, 1957, cover for the Saturday Evening Post, included pitcher Frank Sullivan, tying his shoe on the bench; right fielder Jackie Jensen, No. 18 sitting with Sullivan; catcher Sammy White, at the painting’s bottom left; and Ted Williams, standing by his locker in the middle.

Only Williams did not pose for Rockwell, who added him later by relying on photographs and baseball cards.

The “rookie,” Sherman Safford, was a high school athlete from Pittsfield, Mass., whom Rockwell had asked to be a model.

The painting has belonged to an anonymous owner since 1986, but it is scheduled to go up for auction at Christie’s in New York May 22.

The auction house has put a pre-sale value on the painting of $20 million to $30 million. Last December, Rockwell’s 1951 “Saying Grace” brought $46 million at Sotheby’s.

The season after each of the Red Sox’s recent World Series victories in 2004, 2007 and 2013, the painting has been on exhibit for several days at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

This past week, after six days at the museum, it also was on display at Fenway Park. Sullivan and Safford showed up as part of the painting’s possible farewell tour.

Simpkins doesn’t recall her father ever speaking much about the painting or having to pose for Rockwell. In looking at a copy of the painting online recently, she hesitated a moment in identifying exactly which player was her father, but then recalled it was the player with a hand over his mouth.

The nose seems a bit long for her dad, she says.

Her first memory of “The Rookie” and her father’s connection to Rockwell was when her mother received a jigsaw puzzle of the painting, and the family spent an exciting week at a vacation house putting it together.

Simpkins, 58, says she also has a print of “The Rookie” among her possessions at home.

ggg

Billy Goodman excelled in football, basketball and baseball at Winecoff High School. He was the second of three sons, and his father was a dairy farmer.

In high school baseball, Goodman would pitch one day and catch the next. An old sports editor recalled the right-handed thrower even pitched a game left-handed once and fared pretty well.

Goodman then played for the Concord Weavers in the competitive textile league, whose games were frequented by major league scouts. The Double-A Atlanta Crackers signed him to his first professional contract, and he made the league’s all-star team in 1944.

But World War II led to Goodman’s enlistment in the Navy. He served in the South Pacific theater toward the war’s end and was discharged in June 1946.

By February of the next year, the Red Sox purchased Goodman’s contract for $75,000, and he made his major league debut April 19, 1947, at the age of 21.

Goodman was a full-time player by 1948 and the American League batting champion with a .354 average in 1950. Goodman finished second in the A.L. Most Valuable Player voting that year.

In a Saturday Evening Post feature in 1951, Al Hirschberg wrote that Goodman wasn’t glamorous, colorful, flamboyant and never a magnet for autograph hounds. But he sure could hit.

Goodman ended up with a .300 career batting average over 16 years. In 1,623 major league games, he collected 1,691 hits.

Managers also loved Goodman’s versatility — he could play every infield and outfield position. He spent 11 of his 16 major-league seasons with the Red Sox, but he also has stints with the Baltimore Orioles, Chicago White Sox and Houston Colt .45s.

With the Chicago “Go-Go Sox” of 1959, Goodman played in his only World Series. He went 3 for 13.

ggg

Kathy Simpkins, who was born during a Red Sox spring training in Sarasota, Fla., and grew up there with her parents, mostly remembers Goodman’s coaching days after his playing career was over.

The family often traveled with him in the summers. (Kathy had a brother Robert, now deceased, who was named after Red Sox player Bobby Doerr.)

All the coaches’ and players’ wives and children spent time with each other during the season, Simpkins says, and it was nothing unusual to know Braves players such as Hank Aaron, Phil Niekro and Orlando Cepeda.

“When you’re raised that way, everybody is just everybody,” she says.

Her father eventually left coaching and went into real estate, particularly commercial properties around Sarasota. Simpkins says Goodman had good business instincts and bought up a lot of oceanfront property on which he did well.

“He wasn’t a salesman,” Simpkins said, “but everybody believed him.”

Goodman also spent considerable time hunting and fishing with Williams, the Red Sox great. “He loved my father,” Simpkins said.

Before his death, Goodman played in some old-timers games and helped his high school sweetheart and wife, Margaret, with her antiques business. Margaret died in 2011.

Simpkins says her mother really never got over Billy’s death, and her house in Sarasota was almost a shrine to him.

Billy and Margaret Goodman are buried together in the Mount Olivet Methodist Church Cemetery in Cabarrus County.

ggg

Simpkins says there was never any pretense to Billy Goodman, who had a dry sense of humor, loved to wear ragged jeans and seemed to make friends with everybody.

Simpkins rarely saw her father angry and never witnessed her parents having an argument.

“I’ve never met anybody since like him,” she says. “… He really set the bar high.”

After her divorce in 2006, Simpkins says she felt drawn back to Concord, where she had loved spending parts of her summers at her grandmother’s house on Union Street.

She relocated to Cabarrus County from Maryland, and her daughters Emmy and Callie became soccer stars at Northwest Cabarrus High.

Emmy Simpkins went on to play for Rutgers; Callie, for Duke.

Simpkins says she remains a Red Sox fan, and she knows Boston was the team to which her father felt the strongest attachment. Boston put Goodman in its hall of fame in 2004. Goodman also is a member of the N.C. Sports Hall of Fame.

Safford has said Rockwell paid him $120 to be his model for “The Rookie,” and he used the money to pay for car insurance.

Though her late father is one of the subjects in the noted Rockwell painting, Simpkins won’t have, of course, any financial reward in what it brings at auction later this month.

But when it sells for millions of dollars, maybe her dad will be somewhere, holding a hand over his mouth in amazement.

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-4263, or mwineka@salisburypost.com.