The poet talks to an angel; she responds

Published 12:00 am Sunday, March 30, 2014

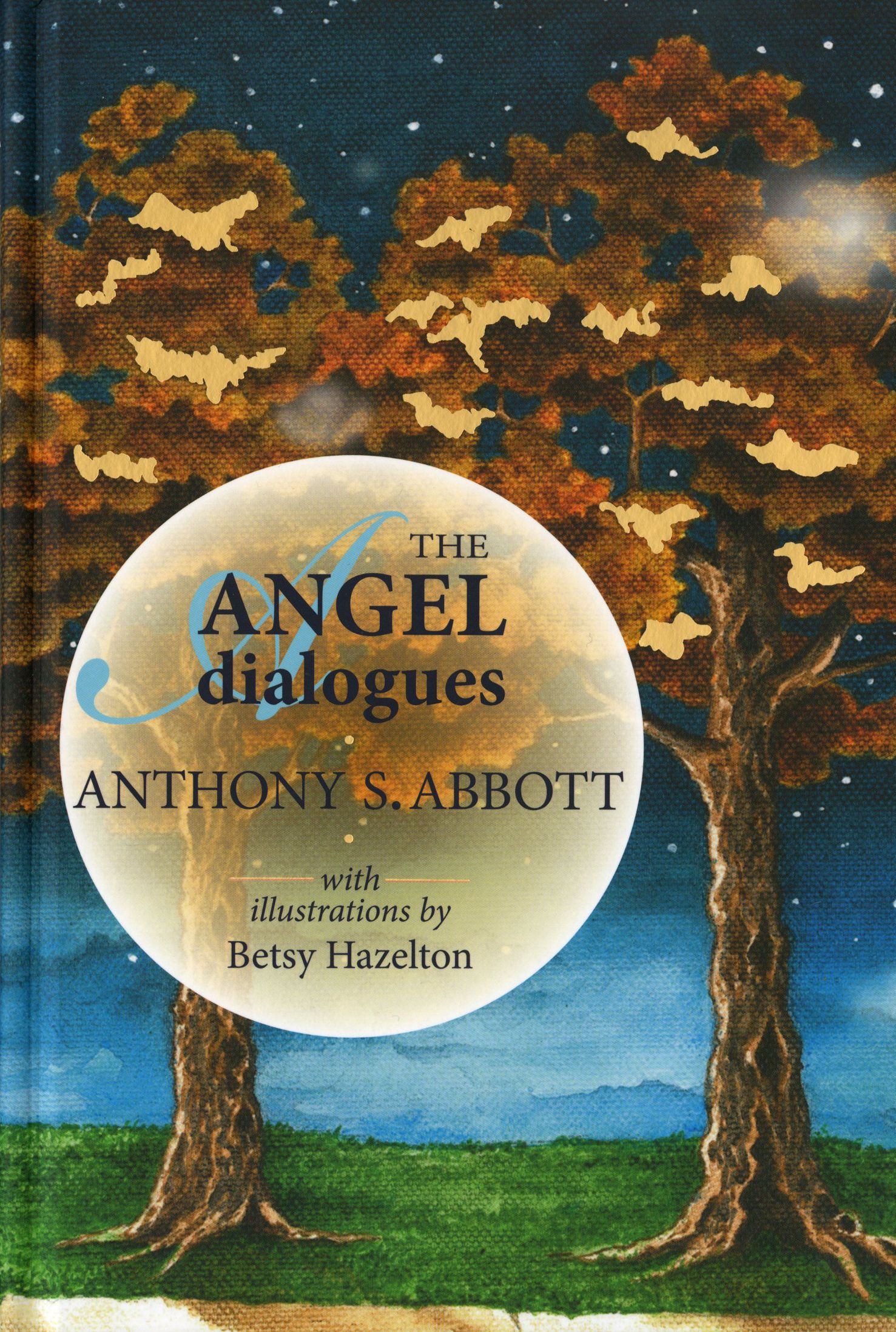

“The Angel Dialogues,” by Anthony S. Abbott, illustrated by Betsy Hazelton. Lorimer Press, Davidson, NC. 2014. 63 pp. $22.95.

“The Angel Dialogues” is like no other book of poetry you’re likely to meet.

First of all, there’s the angel. Then there’s Anthony S. Abbott (Tony to most), the poet himself. Then there’s the dialogue.

Wait, you say, I thought this was poetry.

That’s the beauty of it — it IS poetry and it IS dialogue and the two flow together in a happy burble over the course of a year. The angel does have other things to do, of course.

Abbott loves this new format. Leslie Rindoks, an editor at Lorimer Press, came up with the idea. She designed it and “We decided that there would be two different formats, one of the angel dialogues — every angel dialogue poem has the angel in it, and the angel’s words are in italics, so there’s not so many quotation marks. Then they decided to put the poems the poet writes in like pieces of paper, like a notebook. These poems the poet writes on his own when the angel isn’t present.”

Lofty concept. Interesting to hear the poet speaking of himself as “the poet.”

Abbott says they decided not to do a table of contents, which would be part of any other poetry collection. “It’s a story, a narrative about a story that develops over the course of a year, then ends.”

The poems begin in summer and end in spring.

Rindoks asked Betsy Hazelton to illustrate the book. Hazelton’s golden trees in a night sky will certainly draw readers in, and her angel will surprise you with her curly hair and mischievous smile.

“What I like to think is this is a book that would appeal to all kinds of people,” Abbott says, not just poetry readers. “I want to market it that way. I think it would be a very nice gift, for a birthday or something.”

Abbott’s spirituality comes through strongly in the dialogues, which don’t rely on a defined denomination.

“The poet in his life is pretty discouraged,” Abbott says. The first poem of the book, “The Poet Prays for a Muse,” was originally the last poem. It speaks of “black masks of the hurricanes” and “dreams as grey as the clouds children draw.”

“It was very interesting,” Abbott says. “I didn’t know it was going to be the beginning. It started out as the poet being sad the angel has left, so I rewrote it for the beginning.” It’s here he introduces the mouse you may notice on the inside cover. When the mouse wants to go outdoors, the poet has to open the door. The poet is searching for a muse — with the help of the mouse.

“He’s got to have enough strength to find the angel tree outside,” Abbott says. “She won’t go into the house, and then they walk into the birch wood.”

At the end of the dialogue, they are back outside and the angel is gone. “She’s taken him as far as she can.” But she’s prepared him for her departure. She’s told him he can’t control anything. Angels come when they come; it’s a gift.

“That’s why her name is Grace — she’s a free gift,” Abbott says.

He says the angel works so well because even skeptics sometimes identify with angels. “It’s important to present something spiritual in a way that’s not offensive to non-believers,” he says. He thinks of this work as more in the style of Anne Lamott; “It’s got humor.”

“I’ve done this amazing thing and I’m very excited,” he says. At his readings, he’s had someone read the angel’s parts. Here it will be Janice Fuller, Catawba College professor and poet, and a longtime friend. “Having a character read the angel is a whole new idea. It’s crossing over into theater.”

His audience at a reading in Southern Pines was “blown away by the form of the poem.” Robert Frost, he says, did a lot of poems like dialogue — there are several which have two characters.

You try to explain the dialogue, but it’s still a poem. “Look at the line breaks and language.” It leaps into lyricism when the poet is inspired. The angel tells him he’s on a roll and encourages him to make poems out of experiences.

He uses an Emily Dickinson poem in the book, and the angel says yes, she helped write it. “The whole point is, what’s the difference between the angel and your imagination?”

The dialogue came in spurts. “I think the angel has been with me now about seven or eight years. It started out as a few poems. Once I found her, then she began to develop a personality of her own, a presence of her own. When she came, I wrote what she did.

“When we had Newtown,” the mass shooting of school children, “I knew I had to ask the angel about Newtown” and a poem does that, hauntingly, in this book.

“I think it gives me an advantage to have two voices, because I have to write two parts. It allows you ambiguities. What’s God doing about this? (Newtown). … I loved writing that poem. Then we had the same thing in Boston and I asked the angel if she was in Boston, and we talked about human angels. There’s no difference. We’re all supposed to be angels, to each other, take care of each other. … Like the man in Boston” who used his belt as a tourniquet. “This is what she wants the poet to become when it’s his turn to be an angel, to be there.”

“One of the single most important lessons we can learn is to receive and give. To receive help from angels and give it when it’s needed.”

Anthony Abbott will read from “The Angel Dialogues” with Dr. Janice Fuller at 6 p.m. on Friday, April 4, at Literary Bookpost, 110 S. Main St. He will then sign books until 8 p.m.