Rowan Hall of Famer passes away at 89

Published 12:00 am Friday, January 24, 2014

SALISBURY — While the seating chart for Catawba Hall of Fame inductions wasn’t set in stone, there was a table near the entrance to the lobby that was the unofficial property of two of the most revered men in a room crammed with legends. Joe Ferebee and Vern Benson sat there.

“You’d put those two together and then just kind of get out of their way,” Catawba Hall of Famer Tom Childress said with a laugh. “Ah, the stories they could tell.”

Ah, the stories.

Benson, who passed away on Monday at 89, was modest, humble to the point where you’d never know he spent 57 years in big-time baseball. The pride of Granite Quarry was a major leaguer at 18. He was still scouting at 75. In between, he played, managed and coached all over the map.

He had a favorite personal story he’d share. He told it often and told it well.

It happened in 1951. He was 26 years old then, in his prime, and having the best year of his life for the St. Louis Cardinals’ Triple-A farm team in Columbus, Ohio. He was a strong third baseman on a weak club that would lose 101 times. He had a .308 batting average, 18 homers, 89 RBIs and 111 walks in 138 games.

St. Louis had a third-place team, anchored by future Hall of Famers Stan Musial, Enos Slaughter and Red Schoendienst, but the Cardinals had a hole at third. Someone in the organization decided it was time to give Benson a trial run.

A lefty hitter, he played often after the Redbirds called him up in September. The Cardinals’ lineup started with Solly Hemus-Schoendienst-Musial-Slaughter. Benson normally batted sixth.

But on the final day of that ‘51 season the Cardinals were in Chicago for a doubleheader at Wrigley Field and Slaughter wasn’t in the lineup. Benson was shocked when he stared at the lineup card for the opener and saw manager Marty Marion had scribbled his name in the cleanup spot right behind “Stan the Man.”

Young right-hander Bob Kelly was on the mound for the Cubs and had instructions from manager Phil Cavaretta not to let Musial beat him. In the top of the fifth, Schoendienst drew a two-out walk. Musial was batting .355 with 32 homers, so Kelly threw four wide ones Musial couldn’t reach with a boat-oar and took his chances with Benson.

It was the smart move. Benson made it the wrong one. He probably hit harder line drives in his career, but never a more satisfying one. His double was stroked deep enough that Schoendienst jogged home from second, Musial sprinted home from first and Kelly headed for the showers.

It got better. When Benson scored on a hit by Wally Westlake, Musial greeted him. “Young man, you just showed them who to pitch to,” Musial told him. It was a proud moment that stayed with Benson 60-plus years. His face lit up each time he offered that tale.

•

Born Sept. 19, 1924, the son of a brick mason, Benson played for the Salisbury American Legion team from 1939-41 and likely would’ve been one of the greats in Catawba history. He could field, hit and throw and he could circle the bases in 13.9 seconds.

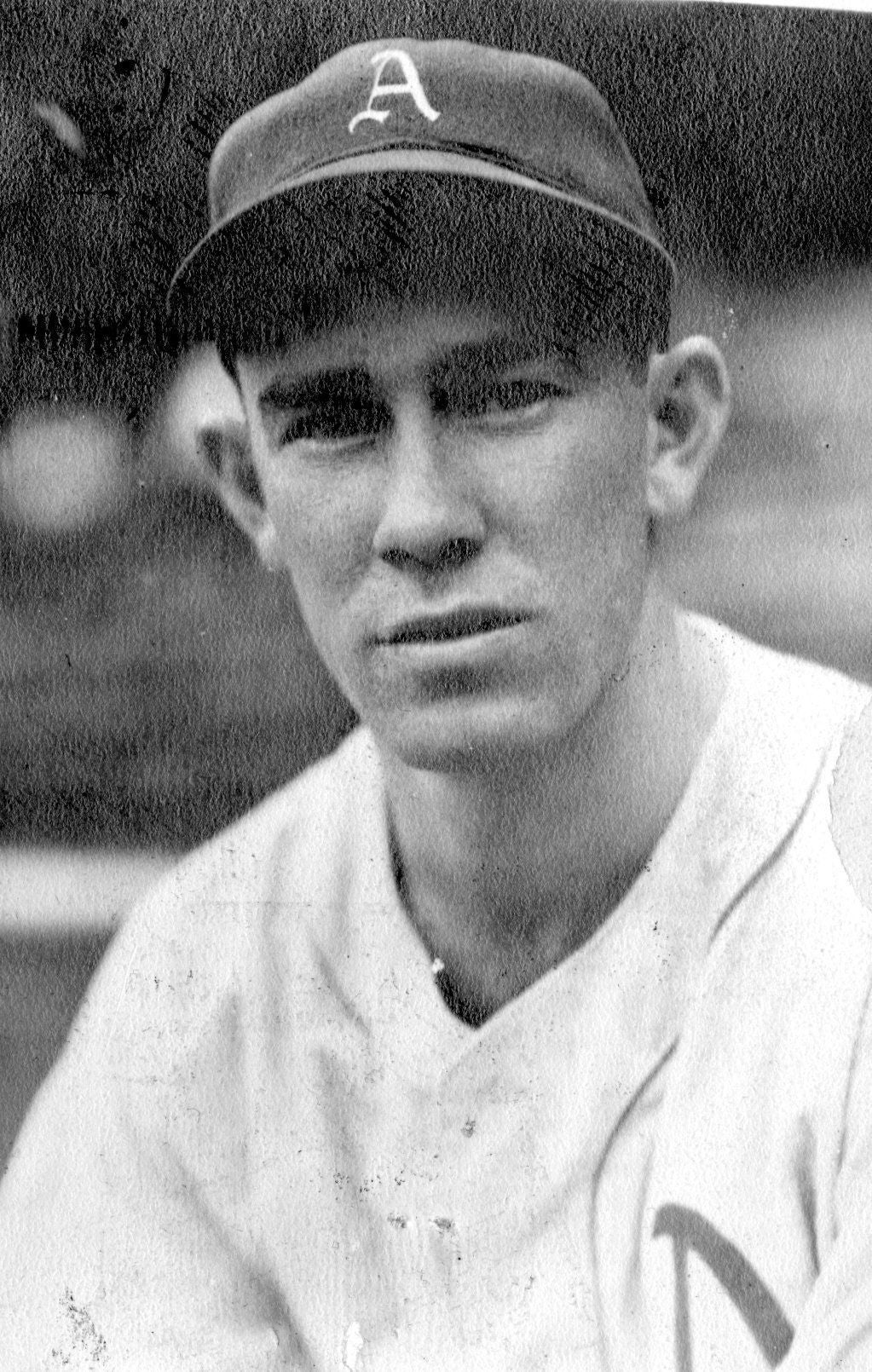

His days at Catawba were cut short, however. Big-league rosters were drained of talent by World War II, and Benson was signed for $1,500 in 1943 and sent straight to the Philadelphia Athletics. Yet to turn 19, he was one of the youngest in the majors. Manager Connie Macks called on him to pinch hit on July 31. He flied out. Benson also went 0-for-1 the next day. Then Uncle Sam intervened.

Like all members of the greatest generation, Benson’s military service was more important than anything he accomplished on a ballfield. He served with the U.S. Army in Europe and returned home with medals.

He rejoined baseball in 1946. He played seven games for the Athletics, but mostly he toiled for farm clubs in Savannah and Toronto. With Toronto, he played against Montreal’s Jackie Robinson.

When the 1946 season ended, Benson was traded to the Cardinals. Three weeks after that swap, he married Rachel Lyerly, a union that would last until her death in 2008.

From 1947-1950, Benson competed in Double-A and Triple A, scratching out a living and waiting for his chance with St. Louis. He got that shot in 1951. It was an eight-year wait for his first big-league hit, but it came on Sept. 9. It was a double at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field off another Vern — Vern Law.

Benson’ first RBI came four days later when he singled off New York’s 20-game winner Sal Maglie. Slaughter charged home from second, beating a throw home by the Giants’ rookie center fielder Willie Mays.

It was on Sept. 18 that Benson walloped his first MLB homer at St. Louis’ Sportsman Park. It came off hard-throwing Brooklyn Dodgers right-hander Ralph Branca. Two weeks later, Branca would give up a somewhat more famous homer to the Giants’ Bobby Thomson that would cost Brooklyn a pennant.

Benson batted .261 in his September look. He had that homer and three doubles, plus a screaming triple off Brooklyn’s Carl Erskine. He’d also showed he could play a big-league left field as well as third.

He was penciled in as the Cardinals’ starter at third base for 1952 and was trying to prove the job was his when he broke his leg sliding into second base in an exhibition game in Sarasota, Fla.

That March slide changed a lot. It was August before he could play again. He hit a homer against the Boston Braves’ Jim Wilson and another off Pittsburgh’s Murry Dickson (both were all-stars), but the bottom line for ‘52 was a .191 average in 20 games. Benson’s days as a prospect were numbered.

In 1953, Benson got only four at-bats with St. Louis. Ray Jablonski seized the Cards’ third-base job and drove in over 100 runs. Benson’s window had closed. He was 28 when he played his final major league game.

It was back to the minors after that. In 1956, Benson became a player/manager and a good one. He piloted the Winnipeg Goldeneyes to the 1957 Northern League crown. He retired as a player in 1959 but managed the Tulsa Oilers to the Texas League title in 1960. He was managing the Triple-A Portland Beavers in 1961 when Johnny Keane was hired at mid-season to manage the Cardinals. Benson accepted a job offer from Keane and became Keane’s right-hand man and third-base coach in St. Louis.

Benson had a role in winning the 1964 World Series against the New York Yankees.

In Game 3. Roger Craig had relieved in the first inning at Yankee Stadium and had pitched brilliantly, but the Cardinals still trailed 3-0 and Craig was due to lead off the sixth. Keane was going to let Craig bat. Benson did his best to talk him out of it.

Benson headed to the third-base coaching box, unsure of what Keane’s choice would be and was thrilled to see Carl Warwick heading to the plate to pinch hit for Craig. Warwick’s single triggered a four-run rally capped by Ken Boyer’s grand slam. The Cardinals won 4-3 and would win the series four games to three.

Keane managed the Yankees in 1965, which meant Benson got to throw batting practice to Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris. But the aging Yanks were on their last legs. Keane and Benson lost their jobs early in 1966.

Two months later, Benson was helping Dave Bristol coach the Cincinnati Reds in the opening act of what would become the vaunted “Big Red Machine.” Benson coached for St. Louis again in the early 1970s and was reunited with Bristol for tours in Atlanta and San Francisco. Benson actually managed one game for the Braves in 1977 after owner Ted Turner sent Bristol on a “scouting trip.” The Braves beat Chuck Tanner’s Pirates 6-1 and Benson always was able to say he was 1-0 as a major-league manager.

Benson managed the Triple-A Syracuse Chiefs in 1978 and 1979 — and ‘79 was a storybook year. Benson’s son, Randy, pitched for Syracuse that season and went 6-4. Syracuse finished second in the International League. Vern was named Manager of the Year for all the minor leagues for that effort.

Benson is a member of three halls of fame — Catawba (1978), North Carolina American Legion (1979) and Salisbury-Rowan (2002). He leaves behind a great family and a legacy far beyond a boxscore that says he had three homers, 12 RBIs and a .202 batting average in the big leagues.