One man cared enough to keep struggling

Published 12:00 am Sunday, September 14, 2014

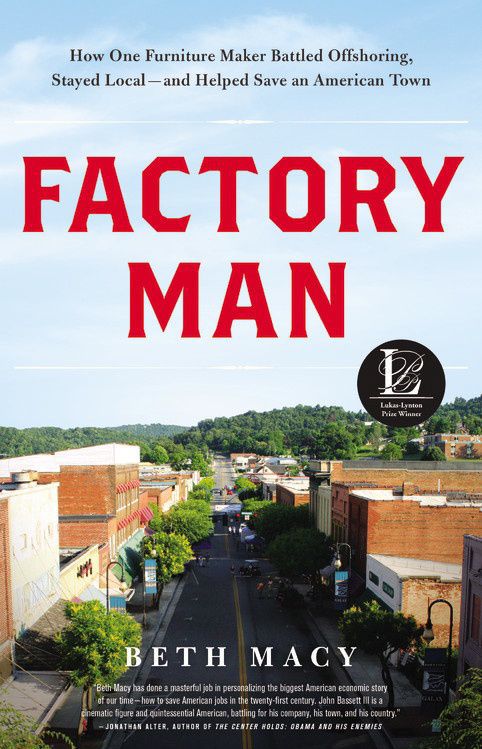

Factory Man: How One Furniture Maker Battled Offshoring, Stayed Local – and Helped Save an America Town,” by Beth Macy. Little, Brown and Co. 2014. 464 pp. $28. Available as ebook.

“What you do is, you put on your business brain and you say, ‘How can I compete in America? That’s what this country needs to do more of, to get off its ass! Look, we do things football coaches do. We don’t do things MBAs do. Don’t make it complicated.’”

In Rowan and Cabarrus counties, we had textiles with a few furniture makers, but if you went across the river into Lexington, to High Point, or headed up into the hills, toward Hickory and on the way to Virginia, you had furniture. Both the textiles and the furniture had come south for the same reasons — raw materials and cheap labor.

When the world opened up, some said for the better, and shipping became cheap, the owners of the textile and furniture factories, places that at one time employed millions and provided the lifeblood for the economies of many towns and cities, looked across the water to where the labor was even cheaper.

First one factory went, then a couple, then a lot, and the more that left the harder it was to make a piece of cloth or a piece of furniture in the South, where it had been done for so long, and compete against the imports. Finally, the owners who fought to remain American companies selling product made in the United States, were few.

Vaughn-Bassett Furniture, led by John Bassett III, was one of them. It still is. In “Factory Man,” author Beth Macy tells the story of this remarkable company led by JB III and the people he hired, how they fought and survived to continue making a product the entire company could be proud of.

Macy is not an author of renown — she is a journalist. She doesn’t work for the New York Times or even the Raleigh News & Observer, but for the Roanoke Times. At the Times she is a winner of national awards including a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard. What became “Factory Man” began as a series of reports she did for her hometown Roanoke newspaper. Macy is the daughter of a factory worker.

Bassett Furniture was founded in 1902 by John Douglas Bassett, JB III’s grandfather, and by the 1960s had become the largest manufacturer of wood furniture in the world. The company would name the town, along with the bank and many other entities where it was, thus, Bassett, Va., home of Bassett Furniture. Eventually, Bassett Furniture would comprise more than 34 plants. Today, there is no furniture factory in Bassett, Va.; there are no furniture factories operated by Bassett Furniture in the U.S.

The history of Bassett Furniture requires a family tree, one populated by some of the greatest names in furniture in America. For instance, there are the Vaughns, who, along with John Bassett, founded the Vaughn-Bassett Furniture Company in Galax, Va., in 1919. Like in many families, there are in-laws and outlaws, and what happened at Bassett Furniture is that JB III’s father, the second John Bassett, died too early. Instead of JB III taking the helm of the huge company, that position went to in-law Bob Spillman.

Over time JB III became less and less important to Spillman; he was sent to Mt. Airy in 1977 to turn around a factory Spillman had bought, and when he returned three years later found himself relegated to a tiny, remote office without even a secretary and beholden to Spillman for every little thing. By 1982 JB III had had enough and resigned, going to Galax, where he headed up the small Vaughn-Bassett Furniture. At this point the stories of the two companies dramatically diverge, and today, Vaughn-Bassett Furniture, still under the leadership of JB III and his sons, employs more than 700 factory workers at its two plants in Galax and Elkin; all except 3 percent of the company’s furniture is made in the United States of locally-sourced materials.

“Factory Man” tells the story of the rise and fall of Bassett Furniture, and the fall and rise of John Bassett III and Vaughn-Bassett Furniture. It is a war story, for John Bassett III has had to battle the Chinese and other countries where low-priced furniture factories operate. He has had to battle the other U.S. furniture manufacturers, who became too easily satisfied with closing factories and having products made overseas, becoming merely importers and idling hundreds of thousands of skilled workers to make an extra dollar, or even a penny. When John Bassett III went to China to find out what he was up against, he went because “you never know how long a snake is until you hold him and stretch him out.” While he was overseas in China, a manufacturer told him, “If the price is right, you will do anything.” John Bassett III would not.

Those two battles must be fought every day. There is a drawer full of domestic battles, many of which JB III has had to fight alone against every acronym the government has ever devised, not the least of which is NAFTA, WTO and still coming, the Pan-Asian Alliances.

Bassett survived for more reasons than his personal determination to save an industry that everyone else was convinced was dying. He had employees who would stand with him. He was one of them, with “sawdust in his blood,” and he knew firsthand every product and every operation, and many of the people in his two factories. He surrounded himself with people who were more than competent in what they did, but excellent, and he didn’t care where they came from. He found his furniture engineer, Linda McMillian, in a Roses store: “She had popcorn grease up to her elbows and no mechanical training at the time, but she worked hard and could do complex geometry in her head — as long as you let her chain-smoke all day long and didn’t make her talk to anyone.” Working for JB III, Linda went from taking a popcorn machine apart to becoming perhaps “the best furniture engineer in the United States.”

There may be multiple reasons why John Bassett III has done what he has with his Vaughn-Bassett Furniture, not the least of which is that he feels deeply for his country, his industry, and for the hills and mountains from which he came. But mostly, he loves his people. When health care costs became so exorbitant that even with the company paying 75 percent of the premium many of the workers wouldn’t participate, first Bassett tore into BCBS for his workers, and then he set up his own free medical care facility for his workers and their families. When some workers even then refused to participate due to fear of what a physical might find, John sent letters to those employee’s wives and told them THEY would lose their coverage if their husbands didn’t have their physicals. “I let Mama take care of it! I let Mama put a finger in their face!” The line of recalcitrant men stretched out the clinic door.

“Our critics have never had to stand in front of five hundred people, like I have, and tell ‘em they’re not gonna have a job. And watch women cry because they don’t know what’s gonna happen to their families or how they’re gonna feed their children. This is not like picking up a telephone from your office on Wall Street and saying, ‘Close factory number thirty-six down in Alabama.’ These are people we look in the eye every day!”

So John Douglas Bassett III, and his sons, and Vaughn-Bassett Furniture, stay strong. They are here now, with two plants the largest manufacturer of wood furniture in the U.S. They never left. Beth Macy puts it all together, making globalization real as she tells the story of the remarkable John Bassett III and his Vaughn-Bassett Furniture Co.