Beautiful voices rise from the darkness

Published 12:00 am Sunday, August 24, 2014

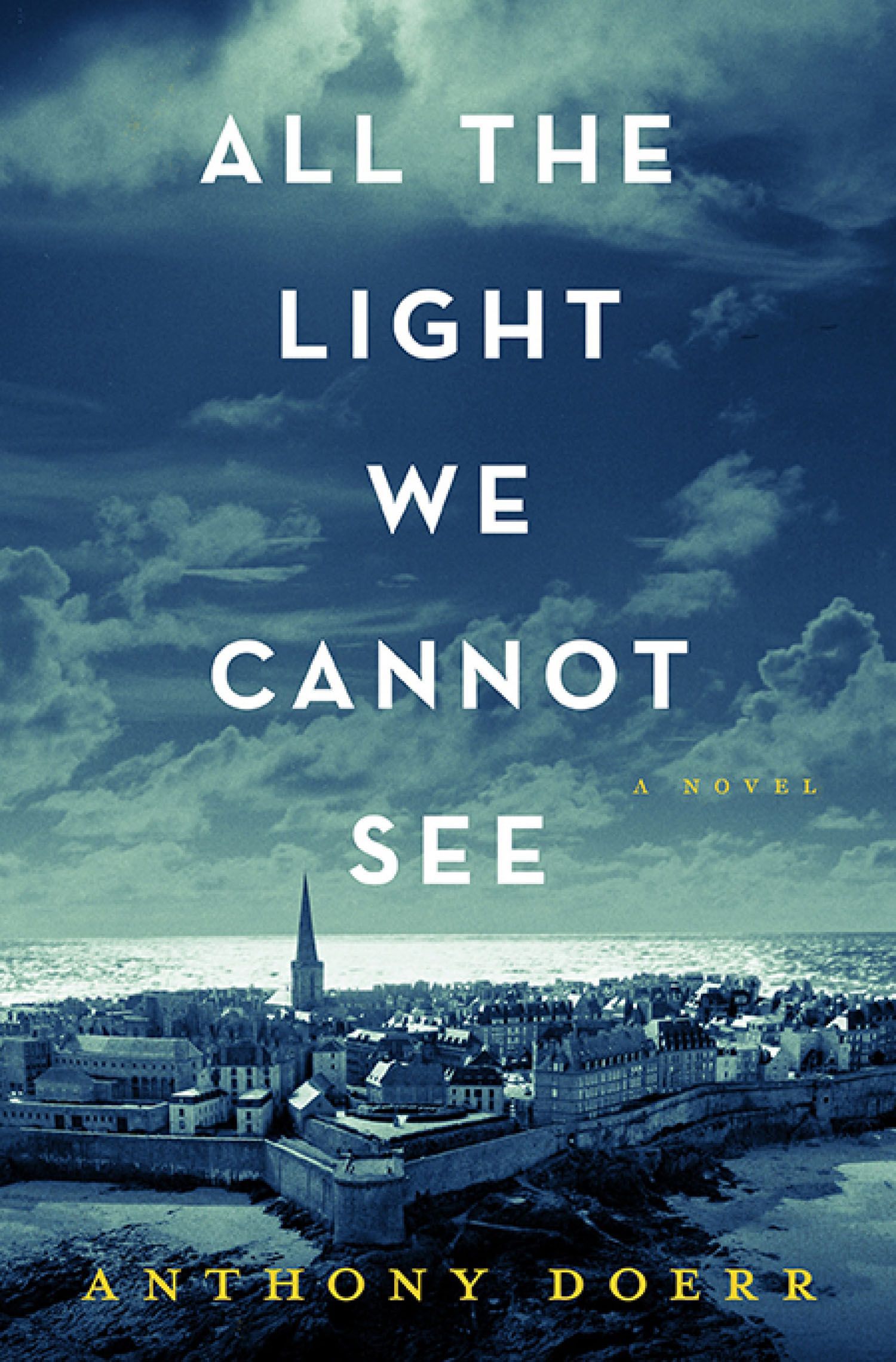

“All the Light We Cannot See,” by Anthony Doerr. Scribner. 2014. 544 pp. $27 hardback. Also an ebook.

You will have the most beautiful visions while reading “All the Light You Cannot See” by Anthony Doerr, and some of the most horrifying.

Doerr follows two children, Werner Pfennig in Germany and Marie-Laure Le Blanc in France as World War II unfolds in Europe. As Werner becomes a soldier and Marie-Laure a refugee, the war marches brutally on.

The brilliance of the novel lies in two simple facts. Marie-Laure is blind. Werner has an uncanny talent for radios, and lives a life of sound.

Doerr doesn’t just write another World War II story, he doesn’t describe the moving fronts, the strategies, the atrocities. He focuses totally on the two children, and the people in their small worlds. He views the war from the eyes of the naive.

And do you think because Marie-Laure is blind that she cannot see? She sees shape and color, she sees music and voices and feelings, better than any sighted person could.

And do you think that because Werner is German he is intrinsically evil? That because of his indoctrination at the strict Schulpforta school he really feels what he is told to feel? Werner at first hides under the strict drills and rules, even forsaking a friend. But in his head, alongside the radio waves, is his sister Jutta, scolding, questioning, until he begins to hear her.

It is inevitable Werner and Marie-Laure will meet, but Doerr takes a long and seemingly relentless path to that finite, incredible meeting. And here, we see what both are made of. “When I lost my sight, Werner, people said I was brave. When my father left, people said I was brave. But it is not bravery; I have no choice. I wake up and live my life. Don’t you do the same?”

“He says, ‘Not in years. But today. Today maybe I did.’ ”

How wise the author is, how tapped into children’s minds. For, in addition to the uncertainties, then the horrors of war, he creates a fairy tale. The tale of the Sea of Flames, an incredible, huge blue diamond with a core of red fire. Legend has it that whoever possesses the diamond will live forever, but the people around that person will all die, strangely, unexpectedly.

Marie-Laure’s father is the keeper of the keys at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, and a master of tiny, intricate boxes that require careful manipulation to open. In order to accommodate his daughter, who goes to work with him most days, he takes her on tours of the museum so she knows where everything is. Marie-Laure finds her way with sounds and smells and atmosphere. He builds her a miniature neighborhood, so that by touching the tiny buildings and tracing the streets, she will know her way.

While Werner and his sister live in an orphanage in a coal-mining town in Germany, Marie-Laure learns to read Braille and pours over “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.” Werner dreads his future in the mine where his father died. Marie-Laure does not think of the future.

Using chapters that alternate between the boy in Germany and the girl in Paris, Doerr also travels around in time, starting in the heat of the war, then going back and forth. The device works in this novel, where it can be distracting in so many others. It gives a sense of hope, perhaps, or a sense that not all will be lost.

When the Germans invade Paris, the museum is desperate to keep the Sea of Flames out of Nazi hands, and makes three copies of the diamond, sending them out with escaping staff members. None knows who has the real stone.

Although the search for the stone is gripping — almost unbearable — and the object is, indeed, a formidable catalyst, the real story is of Werner’s and Marie-Laure’s transformations due to the war.

Werner comes to accept the Nazi teachings, the heartless violence of his world, especially as he becomes a favorite who can fix radios and pinpoint locations through triangulation. At 16, he is in the field assigned to a special radio signal group that travels Europe seeking to crush the resistance.

Marie-Laure lives with her great uncle, Etienne, in Saint-Malo, waiting for news of her father and secretly supporting the resistance with her great-uncle’s radio.

Marie-Laure’s father has been called to Paris, but ends up, like so many others, as a prisoner of war. As hope fades across the continent, as the Germans become more desperate, true atrocities take their toll. And yet, there is so much life in these young people. Marie-Laure, having lived in an insular world, does not fully understand what is going on around her. She understands at a deeper, more essential level, and that’s her message — we must preserve what is essential inside of us. We must focus on the light we cannot see to be a light to lead us into more than survival, into the deep mysteries of what makes us human.

She muses late in life, “And is it so hard to believe that souls might also travel those paths? That her father and Etienne and Madame Manec and the German boy named Werner Pfennig might harry the sky in flocks, like egrets, like terns, like starlings? That great shuttles of souls might fly about, faded but audible if you listen closely enough?”

Doerr uses words so eloquently, so carefully, never maudlin, never excessive. He hones in on his subjects and tells an expansive story from the most basic level. It is indeed a novel to savor. “All the Light We Cannot See” is simply beautiful.